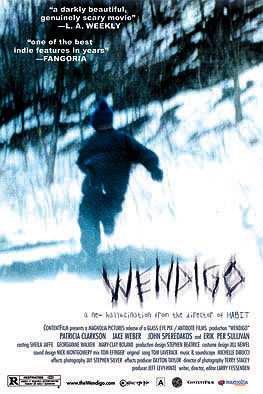

wendigo | cast | crew | notes | press | photos | comic | score | showtimes | trailer | www.theWendigo.com

reviews, excerpts & links

PRINT REVIEWS

VARIETY -Scott Foundas

NY TIMES -Dave Kehr

THE VILLAGE VOICE -J Hoberman

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR -David Sterritt **** (4 of 4 stars)

NY NEWSDAY -John Anderson *** (3 of 4 stars)

LOS ANGELES TIMES -Kenneth Turan

LA WEEKLY -Hazel Dawn-Dumpert

BOSTON PHEONIX - Peg Aloi

THE ORLANDO SENTINEL -Jay Boyar ***** (5 of 5 stars)

THE WASHINGTON TIMES -Phantom of the Movies

THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS -Chris Vognar (B+)

MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE -Colin Covert (3 of 4 stars)

CHICAGO SUN-TIMES -Roger Ebert **1/2 of 4

HOLLYWOOD REPORTER -Frank Scheck

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO -Henry SheehanWEB REVIEWS

HORRORREVIEW.COM - Egregious Gurnow (4 of 4 stars)

AINT IT COOL NEWS.COM -Moriarty

FILMFREAKCENTRAL.NET --Walter Chaw (4 of 4 stars)

TVGUIDE.COM -Ken Fox

FILMCRITIC.COM -Jeremiah Kipp (4.5 of 5 stars)

CINECON.COM -David Korn (3 of 4 stars)

POPKORN JUNKIE.COM -Billy Ray (3.5 of 4)

FEARSMAG.COM -Joseph B Mauceri ("worth $9.08 out of $9.50")

SCIFIDIMENSIONS.COM -Robert Paul Medrano (B)

REELINGREVIEWS.COM -Laura Clifford (A-)

GORGINFOOGLE'S MOVIE GUIDE - Zach (3.5 of 4 stars)FESTIVAL REVIEWS

VARIETY -Scott Foundas

LA WEEKLY -Hazel Dawn-Dumpert

THE WEEKLY PLANET -Lance Goldenberg

FILMFESTIVALS.COM -George Wing

INDIEWIRE.COM-Scott Foundas

CREATURE-CORNER.COM

FESSENDEN PROFILES

TIME OUT NY -Maitland McDonagh

FANGORIA -Steve Puchalski

INDIEWIRE.COM -Anthony Kaufman

FILMMAKERMAGAZINE.com -Mary Glucksman

PHILADELPHIA CITY PAPER -Sam Adams

SALON.COM -Dimitra Kessenides

PAPERMAG.com -Meghan Sutherland

ROCKHARDHORROR.COM

FEARSMAG.COM -Joseph B Mauceri

ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE YEAR! #9. WENDIGO (dir. Larry Fessenden) And that question of what you love gains some measure of added resonance when the object of affection is a father who is distant and clumsy with his affections but a symbol of strength and constancy all the same. Larry Fessenden's Wendigo is the third in the New York filmmaker's trilogy of intimate horror films and his most emotionally affecting by far--judging by the quality of his other work, that's a statement dangerously approaching hyperbole. The late third act transference of the Wendigo figure into the father as avenger--a metamorphosis represented with ingenious basement and in-camera effects--is a series of tightrope maneuvres that shouldn't work but work like a bastard.

--Walter Chaw, FILMFREAK.NET

ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE YEAR! #2. WENDIGO (dir. Larry Fessenden) There is a cutaway to a cooing baby late in the myth-laced horror drama Wendigo that shatters any hope we have of escaping the film's emotional grip. Larry Fessenden is M. Night Shyamalan with a rawer, more personal vision, cloaking as he does piercing societal critique in genre conventions, and that proverbial spoonful of sugar tastes very good indeed. Wendigo is among not only the year's most moving films, but also its most visually sumptuous.

--Bill Chambers FILMFREAK.NET

Scott Foundas, VARIETY (February 5, 2001)

A wonderfully suggestive creepiness permeates every corner of Larry Fessenden's "Wendigo," a mostly superb bit of modern horror from the writer-director-editor previously responsible for the Frankenstein story "No Telling" and the urban vampire pic "Habit." Together, the films comprise an accomplished, unofficial trilogy of urban paranoia, alienation and metaphysical dread. And while "Wendigo" lacks the near-epic introspection and longing of "Habit," it is in many ways Fessenden's most accomplished and accessible pic to date, making strong use of his fine cast and production values in a thoroughly intriguing exploration of our communal need for myths and their need for us. Pic, which should rivet audiences attracted to the more philosophical elements of "The Blair Witch Project" and "The Sixth Sense," could build strong word-of-mouth if not misrepresented as a conventional monster movie.

Like the best, early work of George Romero, Fessenden is experimenting here with the overlapping of real and invented horrors, subtly introducing supernatural elements into a pragmatic setting. He gives us a family, traveling from Manhattan into snowbound upstate New York for a weekend's vacation. And he gives us a father, George (brilliantly played by Jake Weber), who is a violent tempest of internalized stress and unexpressed rage, inextricably chained to his job as an in-demand advertising photog.

The strain on the relationship with his wife, Kim (Patricia Clarkson) is evident, and doesn't go unnoticed by their young son, Miles (Erik Per Sullivan, also excellent).

When George, distracted, runs over a deer in the middle of an iced-over country road, he quickly earns the ire of Otis (John Speredakos), a member of the small hunting party that had been pursuing the now-injured buck. Otis becomes enraged and George, despite pretending otherwise, trembles in his wake.

Once the family has settled at a friend's country home, the evident rural quiet and isolation immediately begin to erode. Otis (who lives on a neighboring property) somehow seems to be at the root of it all.

On its surface, "Wendigo" is easily classifiable as a supernatural horror pic with a withdrawn, solemn child and unstable father at its core. It is a scenario purposely meant to recall "The Shining" and "Poltergeist," but it is only the beginning of what amounts to a questioning of our very conception of horror and fantasy myths. Covering the film with a panoply of textual and subtextual references to icons of cinematic horror, Greek legends and ethnic folklore, Fessenden rips a schism between existential non-belief and more diagrammatic ways of explaining the world. And in the most lyrical scene of the richly textured screenplay, George explains to Miles that all storytelling is but a way of giving meaning to the images and events around us, of distilling virtue from so much chaos and confusion.

The Wendigo, a Native American, shape-shifting spirit capable of taking on any form and combination of elements, is represented as the sculpture of a half-man, half-deer, given to Miles by a mysterious Indian shopkeeper. But really, the Wendigo is a continuation of the suggestion throughout the film of modern man at a crossroads -- of all things primal at odds with all things developed, and of civilized man at odds with his own inner, animalistic self.

In pic's second half, Fessenden further blurs the distinction between reality and myth, spiraling us into a harrowing deluge of panic and fright.

The beauty of Fessenden's technique is that "Wendigo" can be interpreted in any number of ways, and the film is no less enthralling taken as an intricate windup machine of mechanized thrills, as an inquisitive piece of psychological reasoning, or as a deeply perceptive study of a family breaking apart.

In fact, if there's a major disappointment to "Wendigo," it's only that by the time pic reaches its breathless conclusion, you're left waiting for another act. Pic's ending, while perfectly suited to the mythological storytelling being invoked (and sure to provide the fuel for lengthy post-screening debate) comes so abruptly, and on such an adrenaline-racing high, things could continue for at least another reel..

Given the emphasis the film places on the relationship between father and son, the relationship between mother and son, which only begins to take hold in the climactic final moments, craves deeper attention. Fessenden's films have been so perceptive on matters of the male ego, one can only hope he might turn a similar attention to the female psyche.

Pic's tech credits are outstanding, highlighted by Terry Stacey's handsome lensing and the brilliant creature effects, partially designed by Fessenden himself, that combine a variety of stunning photographic manipulations with expressionistic, Jan Svankmajeresque animation.

Hazel Dawn-Dumpert, LA WEEKLY (19 April, 2001)

CRITIC's CHOICE

Eight-year-old Miles (Malcolm in the Middle's Erik Per Sullivan) is on a trip to the wilds of upstate New York with his urban-professional parents (Patricia Clarkson, Jake Weber), when a freak accident and a threatening encounter with a local (John Speredakos) awaken an angry Indian spirit. Writer-director Larry Fessenden third in a series of re-created features begins with a nod to the original WOLFMAN (and a childhood spent adoring it) before shifting into a darkly beautiful, genuinely scary movie about elemental beastliness that lives in even the most civilized among us. Set against Stephen Beatrice's multilayered production design and some deftly measured performances, Fessenden's keen feel for tension and frightful release finds its most refined expression yet.

Dave Kehr, NY TIMES (15 Feb, 2002)

A With-It Way to Jump Up and Say 'Boo!'

The independent filmmaker Larry Fessenden has set himself a challenging project: to approach the themes and thrills of the classic American horror movies through a determinedly modern approach, as if John Cassavetes had been working for Universal in the early 30's.

In his 1991 "No Telling," Mr. Fessenden transposed the Frankenstein story to rural New York; his 1997 "Habit" found vampires in the East Village. In his new movie, "Wendigo," the Wolfman legend becomes the basis for a story of family tension, class warfare and ecological revenge, set again in a snowy, isolated upstate village.

The McClaren family - Kim (Patricia Clarkson), a psychotherapist; George (Jake Weber), a frustrated commercial photographer; and Miles (Erik Per Sullivan), their 8-year-old son - are driving up from Manhattan to spend a winter weekend at a farmhouse borrowed from a city colleague. Just as they approach the property in their tidy little Volvo wagon, a wounded stag leaps out of the woods and smashes into their car.

The animal is followed by three hunters, evidently drunk and quite angry that George has inadvertently stolen the prize they have been pursuing for hours. Otis (John Speredakos), the most unruly of the locals, finishes off the dying animal with a shot from his revolver. George protests, but Otis pushes on, humiliating the city man in front of his wife (who fumes but does nothing) and son (who stares impassively at this first demonstration of his father's vulnerability).

With this opening sequence, Mr. Fessenden introduces several ideas. There is the contrast between the civilized, soft urban male and his macho country counterparts. There is the tension created within the family by George's humiliation. And there is the sudden appearance of nature, red in tooth and claw, and ready to rise up against the human violators, in ways that don't fit into the city folks' Disneyfied notions of a natural landscape of sweetness and sentimentality.

Dramatically, "Wendigo," which opens today at the Film Forum, doesn't do quite as good a job as "Habit" did of putting these ideas and archetypes into play. The script often seems to lose focus in side issues and protracted dialogue scenes. But the core emotions are strong and solid, which serves "Wendigo" well as it moves into the supernatural realm.

The Wendigo of the title is a creature of Indian mythology, an amalgam of animal, vegetable and human components that resembles a very angry tree. A mysterious Indian in the local drugstore offers little Miles a Wendigo figure carved from an antler, giving the boy implicit control over its destructive powers. And when the moment comes, provoked by another hostile act by Otis, Miles is imaginatively able to conjure up the creature and send it out to do his not-quite-conscious will.

As in his previous films, Mr. Fessenden carefully blurs the line between psychology and the supernatural, suggesting that each is strongly implicated in the other. The rampaging Wendigo may be a manifestation of Miles's incipient Oedipal rage, but at the same time it is a force embedded in nature and history. Such abstract notions may put off fans of the genre in its most elemental, slice- and-dice form. But for those in search of something different, "Wendigo" is a genuinely bone-chilling tale.

David Sterritt, CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

Wendigo (R) **** (four stars/4)

Spending a get-away weekend in a borrowed farmhouse, a city couple has an increasingly tense feud with a demented deer hunter, and their eight-year-old son copes with his anxieties through imaginative encounters with a rage-filled phantasm heÍs learned about from an enigmatic Native American sage. FessendenÍs latest horror yarn is a spectacularly smart and scary voyage into the uncanny realm where hard realities, mind-spinning myths, and hallucinatory visions blur into one another at the speed of thought. Produced on a modest budget, it sports moody cinematography, razor-sharp editing, and real-as-life acting that make most of HollywoodÍs big-budget fakery look laughably tame. If you needed proof that understated chills are far more frightening than bursts of bombastic gore, look no further than this spine-shivering example of indie ingenuity.

The nuclear family comes under another sort of terror attack in Wendigo, a nifty supernatural chiller by independent filmmaker Larry Fessenden. A Manhattan professional couple, commercial photographer George (Jake Weber) and psychotherapist Kim (Patricia Clarkson), along with their eight-year-old son, Miles (Erik Per Sullivan), are en route to a winter weekend at a Catskill farmhouse when their Volvo station wagon hits a buck on an icy back road and a subsequent encounter with a hostile hunter (John Sperednakis) turns their getaway into a nightmare.

From the first scene on, Fessenden orchestrates the tensions within the isolated family-George's barely suppressed anger, Kim's resentment, the child's fear of the aggression he senses around him. George frequently teases Miles by playing monster, and before turning in for the night, the boy has his mother check under the bed and inside the closets. (Sullivan's tight, wizened face eerily expresses his parents' middle-aged anxieties.) The old dark house may be rattling in the wind and riddled with mysterious bullet holes, but the locus of terror is the surrounding forest. Like The Blair Witch Project, Wendigo evokes the primal fear of the continent's white settlers-it's named for the malevolent spirit that haunts the woods in Indian legends.

This cannibal creature was used to grisly effect a few years ago in Antonia Bird's gross-out, anti-militarist western Ravenous, but Fessenden's Wendigo is a movie of suggestion and foreboding, most of it filtered through Miles's spooked consciousness. The backstory is provided when the family drives to town for provisions (at a general store well stocked with toy guns and hunting paraphernalia) and a mysterious Native American informs the boy about the shape-shifting wendigo. To add to the historical guilt, George learns that a nearby town was flooded to make a reservoir for New York City. Fessenden finds a landscape of agonized-looking wooden Indians and totem poles, but it's the cold emptiness of the Catskills that seems most uncanny-a vacuum into which the beleaguered family (and the audience) can project their fantasies.

Despite occasional intimations of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Wendigo is more atmospheric than splatterfying. As the story turns violent, Miles's hallucinations come to the fore. Among other things, we learn that Svankmajer's Little Otik may also have been a wendigo: Grounded in Fessenden's handheld camera, stuttering montage rhythms, and time-lapse photography, the engagingly primitive animated special effects contribute to a mood that's sustained through the surprisingly somber conclusion.

Kenneth Turan, LOS ANGELES TIMES, March 1, 2002

Chilling Sprits Lend A Haunting Power to 'Wendigo'

Larry Fessenden is a filmmaker with an uncanny gift for the creation of unsettling moods, capable, among other things, of bringing out the spookiness and menace inherent in a bleak winter landscape. He makes unusual, almost handmade art horror films, of which the eerie "Wendigo" is the latest example.

"Wendigo" is the third film (the excellent Manhattan vampire film "Habit" was the first, "No Telling" the second) in what the writer-director-editor calls "a trilogy of revisionist horror movies" that take a fresh, unencumbered look at some of the classic fright film themes.

In this, Fessenden is an interesting successor to producer Val Lewton, whose much-admired low-key 1940s horror films such as "I Walked With a Zombie," "The Body Snatcher" and "Bedlam" have been enormously influential and admired. And, reminiscent of recent non-American horror films such as Alejandro Amenabar's "The Others" and Guillermo del Toro's "The Devil's Backbone," Fessenden's films depend on atmosphere more than shock to unnerve us. "Wendigo" is named after a terrifying creature out of Native American mythology that has been utilized by everyone from poet Ogden Nash to the creators of "The X-Files" and Marvel Comics. As described in the film by a mysterious tribal elder, this half-man, half-deer shape-shifter is "always hungry, never satisfied. There are spirits to be feared because they are angry. He who hears the cry of the Wendigo is never seen again." If that sentence sends a bit of a chill down your back, you'll appreciate this kind of filmmaking.

Certainly psychoanalyst Kim McClaren ("High Art's" Patricia Clarkson), her photographer-husband, George (Jake Weber), and their 8-year-old son, Miles (the self-possessed Erik Per Sullivan), are not thinking of dreaded mythological beasts as they drive through upstate New York on the way to a vacation weekend at a friend's borrowed country house.

Then, suddenly, a large deer bounds out of the woods and is hit by their car. Almost immediately, a trio of ragged local hunters emerges in the animal's wake, and their leader, the in-your-face Otis (John Speredakos) uses a pistol to kill the buck in front of an unnerved Miles. This causes a disturbing confrontation between the family and the hunters, which gets even creepier when it turns out Otis lives very close to their destination farmhouse.

Though they try, it's hard for the family to have a relaxing time after what has happened, with Kim still angry and George, the kind of guy who has a deer on his sweater, not in his rifle sights, looking especially overmatched. The incident has the strongest effect, however, on young Miles. He's a worried, susceptible child, prone to checking closets for dangerous creatures and in fact visited by ghostly apparitions when the lights go down.

Even in daylight, however, strange incidents begin to happen both around the house and in the town. Is this a case of excitable city folks being unable to cope with the solitude of rural life, or is something strange, something truly sinister, about to go down?

Working with cinematographer Terry Stacey and having the benefit of a wonderfully eerie score by composer Michelle DiBucci, Fessenden is the right director to capture the nuances of this sum-of-all-fears situation.

Making a virtue of necessity, Fessenden manages to use snow, light and wind to create a potent, chilling dreamscape. He employs jagged, almost experimental camerawork in the film's creature sections, which he says he approached "as if I were embarking on an art installation."

Though "Wendigo" has weak spots, including an ending that is not as satisfying as it might be, the film remains memorable despite its flaws. This is a properly spooky film about the power of spirits to influence us whether we believe in them or not.

Walter Chaw, FILMFREAKCENTRAL.COM

**** (out of four)

Larry Fessenden's Wendigo plays like a chthonic rite: it's terrifying in its brutal purity and delicious in its ability to pull domestic trauma into the well of archetype where it festers. The film is a further examination of what William Blake cajoles in his "Marriage of Heaven and Hell"--that "men forgot that all deities reside in the human breast," and it justifies itself beautifully in such a Romanticist discussion, in a Jungian explication, and even in a socio-political and historical examination. Wendigo is an extraordinarily thorny film, no question; that it manages to be so without pretension, while providing an experience that is terrifying and gorgeous, is a remarkable achievement. It's why we go to the cinema: to be fed through the eye, the heart, the mind.

Kim and George (Patricia Clarkson and Jake Weber) drive to a friend's home in upstate New York with young son Miles (Erik Per Sullivan) to spend a winter's weekend away from the worries of their therapist/photographer lives. On the way, their car strikes a buck chased into the road by a trio of hunters (led by the deranged Otis (John Speredakos)); a tense exchange evolves through the kind of country/city baiting perfected in John Boorman's Deliverance. The tension of these opening scenes (and throughout) is simply extraordinary. Even more impressive, however, is Fessenden's ability to mix the objective with the subjective in the narrative, presenting his horror film as a very literal expression of a child coming to terms with the ugliness of adulthood. Miles first bears witness to cruelty and caprice, then appears to become the arbiter of the kind of savage, allegorical justice that defines most mythological maxims.

Wendigo can be viewed on a literal and a metaphorical level. One can take the events of the film at face value or, more instructively, examine how a child constructs his own sensual world. Watch Miles react to his parents' anger and his father's uncomfortable teasing, how a picture book and a bedtime story fuels his night frights, and a moment when Miles wakes from a dream, pauses at the top of the stairs, and leaps across the open space above the landing to get to his parents' bedroom. The level of humanism and observation in this film is revelatory: it captures the fear so often forgotten in films about the cult of childhood, and it presents a character set that is recognizable and utterly convincing in its subtlety.

It's very possible that the entire third act of Wendigo is a projection of Miles' imagination as it tries to incorporate real events with his interpretation of them. In this way, Wendigo joins last year's crop of reality- and identity-testing films--such modern existentialist masterpieces as Memento and Mulholland Drive. By using the film medium to explore the ever-shifting internal landscapes of faith and identity, Wendigo succeeds and satisfies in a way that few films even think to attempt. It is a stunning character piece, a deeply unsettling horror film, and a meticulously crafted clockwork as spare and tight as a drum. Larry Fessenden's Wendigo, the concluding film of a thematically connected trilogy including Habit and No Telling, is a horror film for smart people and one of the best holdovers from last year.

Egregious Gurnow, HORRORREVIEW.COM**** (out of four)

In lieu of an unintentional pun considering the film’s plot, Larry Fessenden’s Wendigo is a stunningly impressive shot-in-the-dark. Aptly labeled as Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining meets John Boorman’s Deliverance, the prowess of the film’s script allured an aggregation of extremely competent, reputable actors, all of which rise to the occasion. The sheer virtuosity of Wendigo--which, if one were naïve in regards to the film’s history, would swear it was the product of Hollywood’s best talents--stands, not only as a great horror flick, but as an outstanding, if not daunting, cinematic effort.

A photographer, George (Jake Weber), his psychologist wife, Kim (Patricia Clarkson), and their son, Miles (Erik Per Sullivan), retreat into the Catskills from their hectic New York lives. En route to the cabin of a friend, George inadvertently hits a deer and is confronted by a band of local hunters, one of which, Otis (John Speredakos), takes issue with the paterfamilias, claiming that the latter took what was rightfully his, that is, the animal’s life. When the family arrives at the cabin the next day, they not only discover that their nearest neighbor is Otis, but that the cottage is mysteriously and ominously riddled with bullet holes. Shortly thereafter, George is victim to another misfortune which will alter his family’s life forever.

The horror genre is stigmatized due to its tendency to eschew characterization in favor of visual spectacle. However, Fessenden’s feature not only compensates for the sins of its horror brethren, it puts to shame most notable dramatic efforts, which rely largely upon the introduction and development of its players. Yet Fessenden accomplishes such while nonetheless remaining mindful of his audience for, while presenting and delving into his various characters and their predicaments, he proceeds to create and sustain an almost unbearable amount of tension and anxiety in his viewers.

From almost the opening frame, Wendigo immediately explores its central characters but, just as we begin to assimilate ourselves to the various personages, Fessenden jars us out of our lull of voyeuristic comfort by having George collide with a deer. Masterfully, when our pulses nearly regain their normative rate, we instantaneously hold our breath as Otis verbally accosts George, which leaves us to mimic the emotional cues from Miles in that we are equally susceptible to the unpredictable tension between the hunter and the family man. Dauntingly, just as we assume that the air around us cannot become any more electrified, one of Otis’s friends pokes a jab at the irate hunter’s pride. We pause, knowing that the only manner in which the woodsmen’s subverted ego can be aptly vented is through George.

This early sequence is representative of the veteran control and concise execution which is Wendigo. As Fessenden continues to flesh out and humanize his characters, he refuses to cast rote, typecast caricatures as each and every figure becomes both empathetic yet reprehensible, making our (and the characters’) forthcoming dilemmas all the more challenging. Wisely, the ambiguous climax leaves everything to the viewer in that George’s undertow of sublimated aggression is succinctly projected via his playful, but psychologically revealing, utterance to his son, “You’re a dead man, Miles” before we watch as he symbolically undermines authority by taking a snapshot of the oblivious Sheriff, Tom Hale (Christopher Wynkoop), in a comprising, embarrassing position. This is cast alongside Otis, whom we first despise without apology before it is revealed that he is acting under the constraint of familial neglect. After introducing this exacerbating information, Fessenden then issues a heart-wrenching scenario in which George--after Kim highlights the need--earnestly attempts to subvert his inferiority complex in order to help his ailing son, who may be the victim of mental instability or merely an overactive imagination, which is prompted and compounded by boredom (he is an only child) and isolation (an urban child stuck in a remote, rural cabin). Refreshingly, even the character of Miles avoids becoming the stereotypical horror demon or vestal victim as the aforementioned possibilities are commingled with the boy’s growing awareness that he can manipulate those around him. However, the gem of the film’s characterization occurs when Tom confronts Otis as the director unnervingly depicts, with an almost brutal simplicity and ease, an interaction of wills as the power structure perpetually shifts upon a mere inflection or a subtle pause.

Yet, for all of the well-rounded, admirable wholeness of its characters, the crux of Wendigo is its theme of violence and retribution. Ingeniously, the perception and subsequent evaluation of whose violence and which party’s retribution is also left to the viewer after Fessenden introduces the motif of violence committed upon nature via its native and current inhabitants, all before offering potential justifications for such, leaving various individuals and factions culpable. After the camera reinforces its archetypical, viable subjects as it pans over the labels of children’s toys in a local drug store in the form of illustrated Indians, G-men toting guns, and settlers keeping wild animals at bay, we are thrown into interpretive conflict in that, though we abhor Otis for much of the picture, we are obligated to admit that he is living off the land while George, symbolic of the city, is a metaphorical antagonist to nature. What cannot be refuted is that the titular character admonishes unnecessary rage, which accounts for his appearance in the presence of all potentially guilty parties during the narrative. In so doing, Fessenden again denies his viewer ready answers.

From a purely technical perspective, Wendigo’s ideas and execution are equally impressive in its masterful use of cut- and freeze-frames, slow motion, POV shots, hand-held sequences, steadicam and time-lapse photography, jump cuts, and montages as the beautiful cinematography is exquisitely brought into a cohesive, aesthetically stunning whole on behalf of Fessenden’s concise editing. Not surprisingly, the gentle--yet maliciously ominous--soundtrack accentuates, but never didactically directs or implies, mood and setting throughout. The only facet of the production which one could legitimately quibble with is that a large portion of the work is grossly underlit.

From almost every conceivable angle, Larry Fessenden’s Wendigo is filmmaking at its best. Not only does the director/writer/editor posit an unrepentantly vague--yet never gratuitously convoluted--ethical conundrum, but he does so while remaining true to the genre as his hyper-empathetic characters project their fears and anxieties upon the audience. Wendigo is an example of pure art and--to most mainstream critics’ chagrin--in all places, the horror genre.

John Anderson, NY NEWSDAY, February 15, 2002

Some Game Running

Dispute over a deer leads to terror in 'Wendigo'(3 STARS) WENDIGO (R). A city couple hit a deer, and their upstate weekend turns into an experiment in terror. Strongly atmospheric, intelligent and just plain scary. With Patricia Clarkson, Jake Weber, Erik Per Sullivan, John Speredakos, Christopher Wynkoop. Written and directed by Larry Fessenden. 1:31 (sex, violence, vulgarity). At Film Forum, 209W. Houston St., Manhattan.

CLASS WARFARE has been a bountiful subtext in this season's movies - "Gosford Park" being the obvious example, but "In the Bedroom," "Monster's Ball" and "The Count of Monte Cristo" all doing their particular riff on the socio-economic- distinction blues.

Leave it to downtown-ist auteur Larry Fessenden, though, to incorporate class conflict as the foundation of a horror movie - and making it the scariest part of the piece.

Fessenden's "Habit" was perhaps the most intelligent and frightening of a rash of modernist vampire films that sort of rose from the crypt of Indie World in the mid-'90s, using the theme of the undead as a metaphor for drug addiction and/or AIDS. "Wendigo" (which follows "No Telling" and is the third in what Fessenden calls his "horror trilogy") is a bit more conventional, using as it does a great deal of time- lapsed skies and hallucinogenic flashes of the grotesque and gory.

But as they drive their Volvo - it had to be a Volvo - though the slate gray dusk of a wintry upstate New York, Kim (Patricia Clarkson), George (Jake Weber) and their timid son, Miles (Erik Per Sullivan, of "Malcolm in the Middle"), are about to run head- on into the beer-fueled resentment of rural America, and find themselves aliens on their own planet.

What they do is hit a deer - a deer that's been tracked for 18 hours by the belligerent Otis (John Speredakos) and his two slightly less venomous pals, chased across the highway and into the front end of the family car. George is rattled, both by the deer and by Otis' anger: The impact cracked an antler, ruining the value of the deer, which Otis dispatches with a pistol shot - thereby sending Kim into a rage, George's adrenaline into flowing and Miles - poor Miles, wonderfully played by Sullivan - into something close to catatonia.

Fessenden eventually winds up with a far more conventional story than this opener implies it will be - the idea of George's manhood being rattled by three guys with guns, and the subsequent weekend being colored by this unexpected confrontation with his ultracivilized ego (he's a photographer), is great stuff - made even better by the thoroughly desolate and accurate portrait Fessenden creates of a specific kind of upstate milieu. Mythic spirituality rears its ugly head - literally - via the title character, based on a Canadian Indian myth (and not the Marvel Comics character, by the way), presumed to be a kind of Druid-like god angered by crimes against nature. And, perhaps, even crimes against people.

That "Wendigo" leaves fewer doors open than you expected it might is almost a disappointment, although the film is a creepshow by any estimation - and, regardless of what end of the Volvo-vs.-Smith & Wesson argument you happen to be on, a provocative piece of entertainment.

Sam Adams, PHILADELPHIA CITY PAPER (May 3-10, 2001)

WENDIGO (recommended)

Larry Fessenden (Habit) has made something of a mini-career out of making brainy films in a horror-film mode. With Wendigo, he gets the balance just right, delivering a film thats thought-provoking and endlessly creepy all at once. Patricia Clarkson (High Art) and Jake Weber play an NYC couple who, young son in tow, make their way up north for a weekend getaway, but promptly find themselves confronted with a rural environment that wants nothing to do with them. Playing off everything from The Shining to Deliverance, Fessenden includes a vengeful hunter who may be stalking the family and an angry American Indian spirit which may be out to either kill or protect them.

Moriarty, AINT IT COOL NEWS (July 30, 2001)

...the theater filled up completely for the evenings second film, and programmer Mitch Davis took the stage to enthusiastically introduce Larry Fessendens WENDIGO. Having seen it now, I can understand Mitchs wild enthusiasm for it. This is a smart, adult feature that stands head and shoulders above most genre offerings in its naturalistic approach to its characters and its subject matter, a supernatural STRAW DOGS that deserves a wide audience when it is released in the US in February 2002.

The start of the film evokes the start of Kubrick's THE SHINING, with the sight of a family in a car, driving through a snowy wilderness. Patricia Clarkson and Jake Weber are Kim and George, and Erik Per Sullivan (Dewey on MALCOLM IN THE MIDDLE) is their son Miles. Hes seated in the back, lost in his fantasy wrestling match between a pair of action figures, a Shogun Warrior and the Wolf Man. Theres a dreamy, languid quality to these opening moments, shattered when George runs into a deer that darts out into the road in front of them. Its sudden, shocking, and the car is sent into a skid that takes it off the road. George gets out of the car to investigate and sees that the animal is still alive, still twitching. Before he can decide what to do about it, three hunters with rifles come running up, and a confrontation unfolds. One of the hunters, Otis (played with a nice sense of restraint by John Speredakos) goes ballistic when he realizes the antler on the buck is cracked. Kim, in turn, freaks out when Otis finishes the deer off with a pistol not ten feet from their car, in plain view of Miles. It's clear from the start that we're dealing with two radically different world views here, and the collision causes instant friction.

It doesn't help that the house George and Kim are staying in is the house Otis grew up in, a house that was sold out from under him by his sister. He takes random shots at the house, and George and Kim find bullet holes in windows, slugs buried in walls. He also spies on them at night while they're making love. In this early movement, it would be easy to think this is just another city folks versus the hicks film, but Fessenden is after something deeper, something more universal than that. This isnt George or Kims movie. Instead, we witness it through the eyes of Miles. This is one of the best movies I've ever seen at capturing the way children interpret the world around them, and that's due in large part to the simple, unadorned work of Erik Per Sullivan. Hes a natural presence, and he never oversells his big moments. He has a remarkable, easy chemistry with both actors playing his parents, and by putting him at the center of the film, Fessenden frees himself up to explore the way a shadow looks on a wall at night or the way things from our days make their way into our dreams and our nightmares.

When the family takes a trip into town for some supplies, Miles has an encounter in a store with an old Indian man who gives him a strange, handcarved statue of a Wendigo, a vengeful spirit. "Just because people dont believe in spirits anymore doesnt mean they arent there," he tells the boy, and Miles begins to carry the totem with him everywhere. The threats to his happiness are from inside the family as much as they are from outside, as George wrestles with his role as a father, trying to understand his son and genuinely listen to him. Its great work by Jake Weber, who looks like the American Tim Roth to an almost spooky degree. Until now, I havent really taken note of Weber, but this is the kind of work that proves an actor is something special. Its not a flashy role, but Weber makes it memorable and real. He and Clarkson are totally believable together, and their fights are as honest as their happy moments. Theres weight and history to this marriage, and Miles is the logical result, a kid born out of real love.

An afternoon of sledding kicks off the films final movement, and theres both tragedy and horror in store for the family and for the locals, Otis in particular. I was impressed by the way Fessenden refused to give any easy answers about the spirit of vengeance in this film. Is it karma? Is it something that Miles summons? Or is it simply dumb luck that touches all of us at some point or another? The film is beautifully photographed, and at no point does there appear to be any limitations on Fessendens imagination due to budget. This is the kind of genre film that deserves real attention when it is released next year, and I hope to bring you more news and interviews regarding the film closer to its actual release.

Film Week, NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO

This is Film Week, Public Radio's program on movies and video. We're joined this week by film critics, Henry Sheehan of the Orange County Register, Jean Oppenheimer of Screen International, and animation authority, Charles Solomon. Our final theatrical film of the week is, Wendigo. The film is set, is it in upstate New York, Henry? It takes a Manhattan family out of the city?

HENRY SHEEHAN: Yes, it, kind of, I guess, what, ten or fifteen years ago, we would have called, a yuppie couple, played by Jake Weber and Patricia Clarkson, and their young boy, who's played by Erik Per Sullivan, who plays the littlest kid on, Malcolm In The Middle. And . . .

LARRY MANTLE: Who's great in the T.V. show.

HENRY SHEEHAN: Yeah, and he's very good. And, he's actually the central character in this movie. I mean, he's, everything revolves around him. And, they're on their way, it's a dark, they're on a, first of all, I have to say, this movie's directed by Larry Fessenden. And, he is, it's a pleasure to watch this movie, because he is in complete control of what he's doing. I mean, this is a, this guy is a film maker. I mean, this guy really knows what he's doing. And, it opens on . . .

LARRY MANTLE: (UNINTELLIGIBLE) make a friend with a big star, so that he could -- (LAUGHTER)

HENRY SHEEHAN: (LAUGH) Yeah, yeah.

LARRY MANTLE: --get the general release movie this week.

HENRY SHEEHAN: This is his third horror film. He, the only, he made one called, Habit, which I saw, and which was also very good. It takes place among drug users in New York City. And, he's kind of like George Romero. Not that his films are like that, but that he's chosen to work in a specific geographic area. In this case, New York City, in New York state, and make films his way. And, he makes, kind of, ghost stories, the old-fashioned way. There's a lot of inference, you know, there aren't too many onscreen monsters, or blood-letting, but it's really spooky. And, this starts off, they're driving down a dark, lonely country highway, they're lost, and all of a sudden a deer crosses the road, and they kill it. Okay, they hit it, and kill it, which is bad enough, 'cause the car ends up in a snow bank. Well, who shows up but three local hunters, with big rifles. And, one of them is really mad because, not only has this couple, George, is the husband's name, killed the deer they've been hunting for eighteen hours, but he's broken one of the antlers, or points, which, you know, was going to look really good on the wall of one of the hunters. And, the hunter's name is Otis. And, here's part of the confrontation they have.

[VIDEO CLIP]

HENRY SHEEHAN: (CONTINUED) So, you know, right away, you know, no ghost, but very scary. You know, are, you know, and you were with the city people. I mean, you feel just as isolated, and as scared, of these, you know, country folk as they are. And, then the movie proceeds, they go to this house they're renting. And, this guy, Otis, turns out to live nearby. And, he always seems to be around when spooky things are going on. And, then, the movie, kind of, starts concentrating on the son, who goes into a store with his mother. And, a mysterious stranger gives them a carving of an Indian spirit, called a Wendigo, which is a soul leader that is always hungry, he says it lives between earth and sky, and it's not angry, but it's always hungry, and it's very fierce. And, I don't want to give too much away, but it's just, if you like, it's just very spooky, it's very chilling, it's just very well done. It's just a pleasure to see a horror movie that actually works, and a film maker that really knows what he's doing.

LARRY MANTLE: So, this film gets, kind of, the arthouse treatment, an arthouse release, and all the crummy horror films end up being released all around the country on thousands of screens.

HENRY SHEEHAN: Yeah, I, yeah, I don't know why, because it's, you know, the, those films are actually failures, because they depend on just, you know, throwing gore up at the screen.

LARRY MANTLE: Yeah, they're gross-out, they're not scary.

HENRY SHEEHAN: Yeah. And, this is very low budget. I mean, there is a little, you do see a little bit of a, kind of a monster thing. But, you know, then, that's not really what makes it scary. It's the humans that make it scary.

LARRY MANTLE: Wendigo, the film. It's by director, Larry Fessenden. Co-starring Jake Weber and Patricia Clarkson, with Erik Per Sullivan. At the Fairfax Cinemas in Hollywood. Rated R.

top | view transcript

Phantom of the Movies, THE WASHINGTON TIMES (December 26, 2002 )

'WENDIGO' TALE OF HORROR SEEN FROM CHILD'S VIEWPOINT

While not quite as powerful as his striking 1997 urban vampire fable "Habit" (A-Pix), writer-director Larry Fessenden's Wendigo, new from Artisan Home Entertainment, rates as a solid, unsettling and, like "Habit," ultimately poignant indie chiller. It's our ...

VIDEO PICK OF THE WEEK

"Wendigo" (priced for rental VHS, also available on DVD) follows an urban family unit - frustrated commercial photographer George (Jake Weber), psychiatrist Kim (Patricia Clarkson) and young son Miles (Erik Per Sullivan, of "Malcolm in the Middle" fame) - into upstate New York's bleakly eerie wintry woods. Their intended long-weekend vacation turns ominous early when they encounter hostile local hunter Otis (John Speredakos) and, later, an American Indian legend about a mysterious evil spirit, the titular "Wendigo."

Since we experience most of the action through Miles' wide, impressionable eyes, we're not always sure how much of what we're seeing springs from his febrile imagination, a technique director Fessenden deftly employs to keep the viewer off balance throughout. Relying more on dark visual poetry than cheap jolts, Mr. Fessenden succeeds in creating a disturbing mood of isolation and mounting dread, one somewhat akin to Stanley Kubrick's "The Shining." The horror, and pathos, heat up in the film's final reel, when Miles' fears take root in a shattering reality.

In his insightful feature-length DVD audio commentary, Mr. Fessenden candidly discusses the movie's varied cinematic influences, ranging from "Psycho" to "Phantasm," and the triumphs and travails of indie filmmaking. Other entertaining extras include a separate Fessenden interview, the behind-the-scenes featurette "Searching for Wendigo," and the original theatrical trailer. Fans of "quiet" horror won't want to miss this one.

Scott Foundas, indiewire.com (May 3, 2001)

IT ONLY HURTS WHEN I LAFF

...And if the (Los Angeles Film) festival was notable for anything, it was for its flat refusal to produce a single film that might be considered a real "discovery." Unless, that is, you count Larry Fessenden's ingenious "Wendigo," which was advertised as a world premiere, despite having shown in a slightly different cut at Slamdance in January. (The primary difference: a few penultimate visual effects shots, tweaked by Fessenden.) No matter -- in any version, "Wendigo" is a sublime evocation of modern man at a three-way intersection of primal instinct, superstition and spirituality It's alternately tender and menacing in a way that turns most "horror" films inside-out, and it's smart enough about families to make "American Beauty" look like "The Family Circus."

Ken Fox, TVGUIDE.COM (February 15, 2002)

...Like Abel Ferrara before him, Fessenden reworks well-trod genre territory to fit his own personal vision, and the results are always interesting. His last two features, NO TELLING and HABIT, turned the hoary Frankenstein and vampire legends inside out to offer smart, socially conscious scares that dealt frankly with environmentalism and addiction. Here Fessenden uses the figure of the shapeshifter to explore the legacy of American violence and the great chain of displacement that began with Native American genocide and continues with the exploitation of rural land by city dwellers. But make no mistake: For all its moral concerns, the film is pretty scary. Rather than going for cheap shocks, Fessenden uses an unsettling mix of montage, time-lapse photography and animation to create an atmosphere of great, unknowable menace that closely approximates the haunted spirit of Algeron Blackwood's unforgettable tale "The Wendigo." These hills are indeed alive.

Chris Vognar, THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS (March 29, 2002)

Wendigo explores the notion of childhood imagination as a force of vengeance and puts forth a troubling question: What's more frightening, the monsters that live in the wilderness or the ones that live in a child's imagination?

A cosmopolitan, New York family George (Jake Weber), Kim (Patricia Clarkson) and their son, Miles (Erik Per Sullivan) are headed to a cabin in the Catskills when they hit a deer. Not only does the family Volvo cheat nearby deer hunters out of a kill shot, but it also damages their trophy. George tries to smooth over the situation, but one of the hunters, Otis (John Speredakos), already carries a deep and personal resentment of city folk. And he's not one to let such a slight go unpunished.

Animosity builds between Otis and George, who's either too proud or too untrusting to approach the local law with his complaints. Meanwhile, Miles receives a carved statuette of a wendigo, a fierce mythical Native-American spirit, from a mysterious old man at a thrift store. As tensions build in and out of the family, the wendigo becomes an escape from and later an unlikely outlet for Miles' fear, anger and feelings of helplessness.

Wendigo isn't yet another examination of the dysfunctional American family gussied up as a horror movie. There's no doubt that Miles is loved by his mother and occasionally inattentive father. One of the most poignant moments comes when George and Miles walk through the snow-dusted woods on their way to go sledding. George recites Robert Frost's poem "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." He and Miles then discuss the deer, its death and what it is to grieve. It's a tender moment between them that foreshadows the tragedy to follow.

Writer and director Larry Fessenden does an outstanding job of generating an ominous atmosphere and summoning the primal fears that stem from isolation. Unseen things may or may not linger behind the trees. Unexplained bullet holes appear in the walls. Hillbillies lurk hither and yon. The woods haven't been this creepy since The Blair Witch Project.

While there's plenty of fine grown-up talent on display, it's young Mr. Sullivan, who's already established a reputation as a weird little kid on TV's Malcolm in the Middle, who serves as the dramatic anchor. Miles is often the center of Wendigo's key scenes, and the little guy does an excellent job of mixing innocence with the brooding, darker side of childhood. Through his performance, Wendigo makes the uncomfortable assertion that the overactive imagination of a child not only conjures the things that go bump in the night, but it also unleashes them upon the world.

George Wing, FILMFESTIVALS.COM (January 24, 2001)

SLAMDANCE DAY FOUR: WENDIGO, THE FIRST BIG HIT JANUARY 24, 2001

"One of the best movies I've ever seen," was one viewer's comment after today's world premiere screening of Wendigo, Larry Fesseden's new feature. Slamdance has its first unqualified hit.

Wendigo, which screened tonight to a sellout crowd, succeeds on every level. The opening scene, in which a New York City couple driving through rural Vermont hits a deer with their car and winds up in a tense encounter with the hunters pursuing the wounded animal, makes it clear that the audience is in the hands of a masterful storyteller.

Fesseden's film seems at first to be an intelligent horror movie, then steadily deepens into a tale of the universal human need to create a mythology to explain the tragedies of life. In this instance, the mythological beast is a half man/half deer spirit of the woods called the 'Wendigo', a naturally benevolent force which responds angrily when human beings get out of line.

The cast is superb, including the lead actor Jake Weber, and the very young Erik Per Sullivan (Malcolm in the Middle). "Erik really was an amazing treasure," said Fesseden, "and that's just what Michael Caine said about working on The Cider House Rules with him. In some ways, despite his age, he was the most professional actor on the set."

The redneck deer hunters who function as the film's human antagonists are portrayed so well as to merit comparison with Deliverance.

At times the film seems to comment on its own style, but always in a subtle way. For instance, there's a moment in which the main character tells his son a Robert Frost poem, then mentions that "Frost had a way of making a simple image seem deep." The film promptly does just that with shots of the Vermont wilderness, including an image of a stream rushing behind a gnarled tree stump, shot with a slow shutter that blurs the water into a airy froth. The director hired a second unit specifically to work on this lovely and surreal photography.

Larry Fesseden has delivered on the promise of his earlier festival hits Habit and No Telling. He has proved himself to be a masterful writer, editor, producer and director, with an accomplished story that will surely find the wide audience it deserves.

top | filmfestivals.com/article

Jeremiah Kipp, FILMCRITIC.COM (APRIL 20, 2001)

****1/2

An old friend took a weekend trip with me to Rhode Island, deep in the woods where I grew up. When night fell, she became instantly terrified by the silence, gripping my arm and asking me to go outside the house and check whether there was anyone out on the lawn.

The imagination is a powerful tool, untrustworthy but also oddly protective. When you're a child, sometimes it's all you have to shield you from the hard, cold facts of reality. Eight-year-old Miles (Erik Per Sullivan, The Cider House Rules) is our perceptive guide into the world of the unknown during a long weekend trip to snowy Vermont. Real danger comes into his path when his father, George (Jake Weber, The Cell), hits a deer, leading to an apprehensive confrontation with angry backwoods hunters. These men with guns want some retribution for losing their prize -- the antler has been cracked. As Kim (Patricia Clarkson, The Pledge) tells her son not to worry, we wonder whether writer-director Larry Fessenden is taking us into unsettling Flannery O'Connor territory.

Wendigo is a slow, steady heartbeat of a horror film that emotionally keeps us in that scary place where bad things can happen. When the family eventually arrive at their cabin, threats linger discreetly under the surface. Walks in the woods, downhill sledding, even a visit to the local village all carry a nearly imperceptible sense of danger. When chopping wood, George turns to Miles and asks, "Do you know how to use an axe?" Be careful, or you might slip.

The thread of parental responsibility emerges as George and Kim struggle to be attentive to Miles, dealing with their own issues as an affectionate but occasionally disconcerted couple. Fessenden takes ample time to develop the family unit, allowing tender scenes like a spelling game between father and son ("Spell onomatopoeia!") to set up a relationship that becomes crucial when his story takes a sharp turn into the uncanny.

At nearly the midpoint of this taut ninety-minute nightmare, relief is found for Miles in the form of a chimerical monster he invents, based on an overheard legend. The Wendigo is an elemental spirit that appears in various guises, taking the shape of wind, trees, or a hungry deer-man with sharp antlers that roams the wilderness. All we can know for sure is that it can fly at you like a sudden storm without warning from everywhere.

When one of the disenfranchised hunters (John Speredakos, in a richly nuanced performance that avoids country bumpkin typecasting) starts lurking around the property looking for trouble, Wendigo transforms into a fever dream collage of frightening images. Miles channels his mystical creation as an instrument of revenge against the forces which might rise up against the family. Traumatic events come full circle in the eerily poetic finale.

Fessenden has built an impressive body of work with a trio of creepy low-budget horror titles. His eco-Frankenstein fable No Telling gave way to the sensual tapestry of dread found in his East Village vampire romance, Habit (one of the finest genre films of the '90s, something my editor would take me to task for, but judge for yourself). Completing the trilogy is Wendigo, ostensibly his "werewolf" movie. The first image is Miles smashing together two dolls, one of them the wolfman and the other a robot. Read the allegory as you will.

Beautifully lensed by the inimitable Terry Stacey (who found more benevolent sides of nature in Tom Gilroy's Spring Forward), Wendigo achieves a lyrical quality that comes close to the fabric of dreams. The peculiar stop-motion tracking shots through wilderness blur into a mosaic of haunting textures, complemented by the hard folk beats of Michelle DiBucci's score. Credit should also be extended to the surreal Wendigo designs (created by Fessenden, supervised by Tim Considine), hand-crafted effects that could never have been achieved through the limitations of computer generated imagery.

The greatest magic trick Fessenden pulls out of his hat is the stunning performance by Erik Per Sullivan, blessed with a face that conveys so much while seeming to do so little. There's something both old and young in his features, possessed with the bright-eyed intelligence of, well, maybe a young Larry Fessenden. Wendigo was inspired by a story told by the filmmaker's first grade teacher that scared Young Larry. Hey, thanks a lot, Lar -- you scared the shit out of me, too.

Human behavior can be disconcerting, even cruel. We grow afraid of the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to, so stories are created as metaphors or reflections to help us deal with it. Sometimes, humor can be cathartic, laughing at our own humiliation or pain, but Fessenden chooses to take us to a darker realm. Wendigo is a mirror of our psyche, the place we're otherwise too afraid to go.

Jay Boyar, THE ORLANDO SENTINEL, June 13 2001

HHHHH

A FRIGHT UNSEEN -- FOREST OF FEAR

The difference between a lousy horror movie and a first-rate one is often a matter of style.

Plot and characters that seem corny in a horror flick with no style can totally creep you out if the filmmaker knows his stuff.

Larry Fessenden is credited as the writer, director and editor of Wendigo, and it's that last credit that may be most telling. Mixing fast-motion, slow-motion and supercharged jump-cut techniques, Fessenden (Habit, No Telling) sets a chilling tone of anticipation that keeps you inching forward, a scene at a time, until you're on the edge of your seat.

The premise is fairly straightforward.

A sophisticated New York couple and their 8-year-old son are driving upstate to spend a weekend at a friend's country farmhouse. They hit a deer, angering a dangerously weird hunter who'd had it in his sights. Later, the boy finds a doll that represents the half-man, half-deer Native American spirit called the Wendigo.

Just about everything in this film works. The plot is well thought-out and the dialogue sounds realistic. It's touching and true-to-life the way the parents (Patricia Clarkson and Jake Weber), at every awful turn, try to shield their son from the worst.

The acting is top-notch, including that of young Erik Per Sullivan (Malcolm in the Middle), who, as the boy, seems to have been cast for his big, anxious eyes and satellite-dish ears.

Finally, however, the movie comes down to its exciting style, and the creepy mood that that style makes possible.

If a horror movie isn't creepy, it isn't much of anything. And if it is creepy, it doesn't need to be much of anything else.

Lance Goldenberg, THE WEEKLY PLANET, June 13 2001

a real shocker in its own right, is Wendigo (June 13, 9:45 p.m.), the latest project from independent filmmaker Larry Fessenden. There's a touch of The Shining and more than a little Deliverance in this taut little psychodrama about a snowbound, vacationing family being traumatized by psycho rednecks out in the middle of nowhere. Is it this year's Blair Witch Project? No. Are some of the effects a touch too artsy while others just come off as overly cheesy? Well, honestly, yes. But that doesn't take away from the notion that Wendigo is still one of the more frightening and disturbing movies I've seen in quite some time.

Jordana Brown, CITYSEARCH.COM, FEB 15 2002

The mainstream horror genre could learn something from this austere indie about an urban family finding horror in the country. Rated:ÊÊ ÊÊÊ Things get creepy for the McLaren family on the drive to a friend's rural farmhouse: The family car hits a deer, which upset some local hunters, and soon they all face supernatural retribution.

With its tale of an urban family in a stark winter setting and facing ticked-off locals in plaid flannel, "Wendigo" could easily have been a mere blend of "Deliverance" and "The Shining." Instead, it's a beautiful and haunting examination of the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of the mundane horrors of the world. Writer-director Larry Fessenden paints an ultrabelievable portrait of the moments in a young family's daily life, and his script is bolstered by excellent performances that give the characters heft and hint at their history together. "Wendigo" practically hums with foreboding anxiety and tension, but it's also as subtle as the quietly sinister wind that accompanies almost every shot.

Colin Covert, MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE

'Wendigo' freshens up horror genre

*** out of four stars

Published Apr 19, 2002

The spirit of Stephen King wafts over "Wendigo" like a chilling breeze at your neck. The spooky backwoods New England locale, the damaged protagonist, the narrow-eyed locals and the child whose night frights could be warning visions are all familiar enough. But writer-director Larry Fessenden makes them feel as fresh and creepy as a newly dug grave.

A Volvo wagon snakes up an icy country road. It's the beginning of a weekend getaway at a friend's farmhouse for Manhattanites George (Jake Weber), Kim (Patricia Clarkson), and their 8-year-old son, Miles (Erik Per Sullivan). They hit a buck and spin into a snowbank, where they're accosted by an angry hunter, Otis (John Speredakos). The city people spoiled his trophy, cracking the valuable antlers. George and Otis lock horns like battling stags in front of Miles' spooked eyes. An atmosphere of tension and foreboding is established swiftly and believably.

We get to know the characters one layer at a time. First, we register George's tightly contained anger in his exchanges with Kim, his confrontation with Otis and his monster-play with Miles. Little by little, Fessenden reveals George's money worries and professional setbacks.

We discover that high-strung Kim is a therapist. It's both surprising and logical. Who else would take on a fixer-upper like her husband?

We see much of the movie through Miles' experience, going back and forth between our sympathy for his parents and our fear that they're doing more damage to him than any woodland threat could ever do.

On a trip to town, Miles hears the legend of the wendigo, a vengeful spirit said to haunt the region. His nightmares increase, but there's danger in the daylight, too: bullet holes in windows and walls. Is the family being threatened?

The uniformly strong cast lends credibility to the engrossing predicament. Weber, an actor with an edgy, hostile presence, is perfectly cast as the simmering father, and Speredakos has the glint of "Deliverance" menace in his eye. Sullivan, the youngest brother on TV's "Malcolm in the Middle," proves he's a solid dramatic actor, giving Miles a heartbreaking look of wide-eyed worry.

Fessenden makes a last-minute detour into horror-film territory that can be read as hallucination. It's a risky maneuver that might spoil the film for some viewers. By the time the misstep arrived, I was too impressed with the film to complain. Missteps and all, Fessenden is a talent to watch.

wendigo | cast | crew | notes | press | photos | comic | score | distribution | trailer | www.theWendigo.com