HISTORY LESSONS (2013)

HORROR MOVIES.CA November 18 2013

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY August 17 2013 by Clark CollisBENEATH RELEASE (2013)

USA TODAY June 23, 2013 by Brian TruittRECENT ARTICLES (2012)

THROUGH A GLASS EYE March 2, 2012 by Danny Trudell

ELECTRIC SHEEP Dec 16, 2011 by Alex Fitch

STAKE LAND RELEASE (2011)

NEW YORK TIMES ARTS AND LEISURE April 15, 2011 By ERIC KOHN

RETROSPECTIVE (2010)

WALL STREET JOURNAL Oct 21, 2010 by Steve DollarSACREFLIX SLATE (2009-10)

THREE FILMS BY LARRY FESSENDEN 22 March 2010 by Giles Edward

GOLDEN HAMMER AWARD Dec 09, 2009 by Mike Ryan

FEAR ZONE December 02, 2009 by Brian J. Showers

FILMMAKER MAGAZINE October 2009 - Lauren Wissot

ALL THINGS HORROR October 29, 2009 - Chris Hallock

I SELL THE DEAD (2008-09) press

ONION A.V. CLUB August 31, 2009 - Sam Adams

QUIET EARTH Oct 28, 2008- Dr. Nathan

ICONS OF FRIGHT July 2008

FEAR ITSELF (2008) press

FANGORIA - Michael Gingold

FEAR ZONE - Gregory Lamberson

MONSTERSANDCRITICS - April MacIntyre Jul 30, 2008

THE LAST WINTER (2006-07) press

HOLLYWOOD REPORTER Sept 6, 2006 - Greg Goldstein

CINEMASCOPE Dec 2006 - Adam Nayman

FANGORIA, August 2007 - Don Kaye

THE NEW YORK SUN Sept 14, 2007 - Steve Dollar

THE REELER Sept 17, 2007 - S.T. VanAirsdale

RAY PRIVETT BLOG Sept 19, 2007

INDIEWIRE INTERVIEW Sept 19, 2007

L.A. WEEKLY Sept 19, by Judith Lewis

FILMMAKER Sept 18, 2007 by Damon Smith

SHOCK TIL YOU DROP 2007 by Edward Douglas

MAN OF NEW YORK CITY CINEMA 2007 by Ray Privett

IFC NEWS 2007 by Aaron Hillis

ENTERTAINMENT INSIDERS Sept 9, 2007- Adam Barnick

FEAR ZONE 2007 by Joseph Fusco

THE HOUSE NEXT DOOR 2007 by Jeremiah Kipp

PHILADELPHIA CITY PAPER 2007 by Sam AdamsWENDIGO (2002) press

TIME OUT NY, Feb 7-14 - Maitland McDonagh

NEW YORK MAGAZINE, Feb 18, 2002 - Ben Kaplan

FANGORIA, January 2002 - Steve Puchalski

FILMMAKER, January 2002 -Travis CrawfordHABIT (1997-98) press

VILLAGE VOICE, June 10, 1997 - Amy Taubin

BACKSTAGE WEST, May 1, 1997 - Jamie Painter

L.A. WEEKLY, Oct31-Nov 6, 1997 - Hazel-Dawn Dumpert

TIME OUT New York, November 13-20, 1997 -Andrew Johnston

CUPS, October 97 -Alexander Laurence

FANGORIA, November 97 -Steve Puchalski

ALBANY TIMES UNION, April 17, 1998 -Amy Biancolli

VENT MAGAZINE May 1998 -Don Philbricht

GUERRILLA FILMMAKER Winter 99 -Bruno Derlin

NOVEMBER 18 2013, POSTED AT HORRORMOVIES.CA

In this multi-part series we will be investigating the next wave of horror. The directors, actors, and producers of the current independent horror movement have formed a collaborative community. While their subject matter changes from project to project, the push for realism and characterization propels these films into a new category of horror. They have been labeled as “Mumblegore” films and also as a collective been called “Splat Pack Jr.” but I like to refer to them as Next Wave due to their link to French New Wave cinema.

In both sub-genres there is a camaraderie between the films and their makers. Goddard and Truffaut traded actors in the same way Adam Wingard and Ti West do – lets just hope Wingard and West don’t get into a career-long feud. Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer, Chabrol, and Rivette were all critics for the Cahiers Du Cinema which was co-founded by Andre Bazin, and through Cahiers they were able to tear apart France’s beloved classical style. Bazin is best known for giving the world auteur theory which states that the director is the author of his film and that there is a personal signature that permeates his work. Under the tutelage of Bazin and an iconoclastic feeling for current cinema, they set out to destroy preconceived notions of what films should be. By using improvised dialogue, portable equipment, miniscule budgets, themes of existentialism, genre mixing, and narrative ambiguity these renegades became some of the most influential filmmakers of all time.

Roughly 55 years later the concepts introduced by New Wave have infused themselves into the most unlikely place – horror. Adam Wingard, Ti West, Joe Swanberg, Simon Barrett, AJ Bowen, Amy Seimetz, E.L. Katz, David Bruckner, Dan Bush, and Jacob Gentry are all currently involved in the shift of the horror paradigm. These artists are proving again and again that Hollywood horror is a thing of the past. By telling smaller and more personal stories the audiences are beginning to turn their backs on the remake machine. Between V/H/S and You’re Next all of the Next Wave has collaborated together, and it may have not been made possible without horror’s underdog Larry Fessenden. This leads us to our current Horror Spotlight.

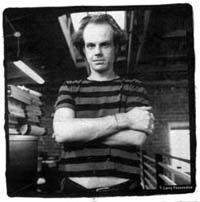

Larry Fessenden

Fessenden made a name for himself in the mid-nineties with Habit (1995). Between Habit and Abel Ferrera’s The Addiction, there was a movement toward vampire realism, though it did not last (we eventually got stuck with Twilight but that’s a different rant entirely). It seemed as though Fessenden was striving for a cinematic vision of the disintegration of humanity. This theme would later pop up in Wendigo (2001), The Last Winter (2006), and most recently in Beneath (2013). All of Fessenden’s films fly below the radar but provide original stories through low budget means. Although his directing credits are rather slim, it is his role as a supporter of the arts that makes Larry an extremely important figure in recent horror.

As a producer and owner of Glass Eye Pix, Fessenden helped Ti West with his debut The Roost (2005) and continued supporting him with Trigger Man (2007), House Of The Devil (2009) and The Innkeepers (2011). He also produced Jim Mickle’s Stake Land (2010) who has gone on to make the We Are What We Are (2013) remake. Fessenden produced and stared in I Sell The Dead (2008) which was Glenn McQuaid’s debut as a feature filmmaker. Fessenden and McQuaid are also the creative team behind Tales From Beyond The Pale, a horror radio show with two seasons available online. McQuaid began as a visual effects artist on Ti West’s The Roost and eventually went on to direct a segment of V/H/S (2012). Glass Eye Pix has two documentaries releasing this year, the George Romero doc Birth Of The Living Dead and American Jesus.

Fessenden shows up everywhere as an actor, but mostly in anything indie-horror related. He worked with Ti West and Eli Roth on Cabin Fever 2: Spring Forever (2009) which also featured Joe Swanberg in a tiny role as well. Ti and Eli formed their friendship through the production of Cabin Fever 2 and this eventually led to Eli Roth producing West’s The Sacrament (2013). Fessenden appears in Joe Swanberg’s Silver Bullets (2011) and All The Lights In The Sky (2012). Jeremy Gardner also had Fessenden provide a menacing voice on the radio in The Battery (2012). He recently starred in Chad Kinkle’s Jug Face (2013) and of course had a role in You’re Next.

Larry Fessenden’s penchant for realism within his own monster films makes it only fitting that he has lent himself to horror’s Next Wave filmmakers. With two decades of experience in the horror genre, he has never passed up an opportunity to show corrosive institutions and the folly of hubris. These elements are again featured in Tales From Beyond The Pale which brings together the writing talents of Simon Barrett, film theorist Kim Newman, and Glenn McQuaid. Beyond The Pale also teams Fessenden with the voices of Joe Swanberg, Amy Seimetz, and AJ Bowen to name just a few.

In an interview with Eric Stanze from Fearnet, Fessenden describes what his segment of ABC’s Of Death 2 will be about, “sex, death, the pointlessness of it all. My usual concerns!” During his fascinating career, Fessenden has shown time and time again that the truly diabolical nature of mankind is what drives the horror genre. Audiences could care less about the often sympathetic monster or the film’s survivors, they want their suspicions about despicable people brought to life. Fessenden has created in his body of work a nihilistic landscape that, unfortunately, we can all relate to.

Fessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

'You're Next': How a group of indie filmmakers produced

one of 2013's most terrifying movies of the Year

By Clark Collis on Aug 17, 2013EXCERPT:

...

But some horror filmmakers have ploughed their own bloody furrow, and few more independently than Larry Fessenden. The New York-based Fessenden resembles a younger Jack Nicholson in a world without dentistry — the director was mugged in 1985 and lost an upper front tooth he has never replaced — and his movies are equally idiosyncratic. The filmmaker’s first notable release was 1995’s Habit which starred Fessenden as a heavy-drinking restaurant manager whose new girlfriend might be a vampire. Made for $60,000 this grungily erotic film spends far more time exploring the lives of its downtown New York-dwelling cast of characters than it does the possibility a bloodsucker is dwelling among them. Although the film received an extremely limited release it greatly affected You’re Next writer Barrett, who saw Fessenden introduce a screening of Habit while he was a film student at Ithaca College. “When we were growing up he was one of the few American guys doing these weird genre hybrids,” says Barrett. Wingard too was impressed by Fessenden’s film. The director says it was a “huge influence” on his own early work, including 2007’s drug-fueled, sort-of ghost story Pop Skull.

Fessenden hasn’t just supplied inspiration—through his Glass Eye Pix production company he has helped mentor filmmakers such as Old Joy director Kelly Reichardt (whose 1994 debut, the drama River of Grass, Fessenden starred in and edited) and Ti West. In the early oughts, West attended New York’s School for Visual Arts and was the only “horror kid” in a class taught by Reichardt who brokered an introduction to Fessenden. The pair hit it off and Fessenden funded the filmmaker’s first film, the minimalist, bats-centric The Roost. “He said, ‘If I gave you a little bit of money, could you just go do it with not a lot of help?’” says West. “I probably lied and just said ‘Yes.’ So he gave us $50,000 and we made the Roost.’”

The Roost premiered at the South By Southwest Film Festival in the spring of 2005 but earned a mere $5,000 on its own limited release that fall. However, Fessenden’s Glass Eye Pix company backed several of West’s subsequent projects, including 2007’s Trigger Man, and 2009’s House of the Devil, a note perfect homage to ‘80s horror for which Lena Dunham, a friend of the director, voiced the role of a 911 operator. Dunham is also a friend of Seimetz and worked as boom operator on her 2009 short film Round Town Girls, which Seimetz codirected with Ronald and Mary Bronstein. “Lena was right out of Oberlin and she was a fan of Ronnie and Mary,” says Seimetz. “Mary and I had written this movie and Lena wanted to come on and just help out any way that she could, so she boom-opped for us. But she was so bad at boom-opping! The sound was incredibly bad and the boom was in the shot, or not close enough. I mean, here’s the thing: She was obviously destined for greater things.” Seimetz, in turn, worked as boom operator on Dunham’s web series Delusional Downtown Divas and then appeared in her big screen directing debut Tiny Furniture, whose credits thanked West.

In what would become something of a trope-cum-running gag for the mumblegore crowd West gave Fessenden cameos in his movies, appearances which frequently ended with the death of his character. “Yeah, we keep joking [about that],” West says. “He’s like, ‘You have to kill me! It’s been a while since you’ve killed me in a movie!” For his part, Fessenden says he is genuinely perplexed as to why so many people he has helped would wish him harm, at least onscreen. “I’d like to know!” he laughs. “I try to be polite and pleasant but somehow they see my face and they just want to mangle it, one way or another — which I’ve already done on my own, but they want to put in the final punch.”

When he was at SXSW with The Roost, West met Joe Swanberg whose own debut film, Kissing on the Mouth, was premiering at the festival. Swanberg’s movie, a sexually explicit rumination on post-college life, shared little with The Roost other than a micro-budget. However, the pair became friends and Swanberg cast West alongside Seimetz in his 2011 film Silver Bullets, about an actress who gets a part in a werewolf movie. By the time he was making Silver Bullets Swanberg had become well-known in the indie community as one of the leading lights of “mumblecore,” a loose grouping of filmmakers whose movies had low budgets and naturalistic vibe and whose membership included director Andrew Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha, this year’s Computer Chess). Other mumblecore notables include Greta Gerwig and Mark Duplass, both of whom starred in Swanberg’s best known film, 2007’s Hannah Takes the Stairs. The pair would soon explore the world of terror themselves: Duplass and his brother/co-director Jay cast Gerwig in 2008’s Baghead, about a group of actors whose horror movie idea invades their real-lives and the actress also appeared in West’s House of the Devil. In time, the term “mumblecore” spawned a dark sibling, “mumblegore,” a phrase used to denote those occasions when Swanberg, Duplass and other mumblecore-affiliated directors made a genre movie. Adam Wingard, whose films have appeared on lists of “mumblegore” movies says he is genuinely ambivalent about the phrase: “I don’t care. I think mumblecore is such an obscure term [that] if somebody calls You’re Next mumblegore people would probably be even more confused. But that’s totally fine with me. Mumblecore is still the best way to describe that world we came from.”

...

In 2010, Travis Stevens founded Snowfort Pictures, a boutique film production company specializing in what the executive describes as “elevated genre films. We’re really focused on finding emerging talent — filmmakers that have an interesting eye and some fresh ideas.” Snowfort’s debut movie was the first film Wingard and Barrett worked on together, A Horrible Way To Die. “We kept up with each other over the years,” says Barrett. “Simon really like my movies and I was always a big fan of his screenplays. My career was going nowhere, necessarily, and his career had been knocked down to nothing. So, [we said] ‘Let’s do this mumblecore film.’” The film starred Swanberg, who Wingard had met at the Sidewalk Film Festival in Birmingham, Ala., and Seimetz. The director had been impressed by the actress’s performance in 2010’s Bitter Feast, a horror movie about a vengeance-seeking sous-chef produced by, and costarring, Larry Fessenden. For the crucial role of Seimetz’s homicidal onscreen husband Wingard recruited actor AJ Bowen, another Horrible cast member who would return in You’re Next.

Just as Fessenden’s Habit can barely be considered a horror film, A Horrible Way To Die often seems less interested in slaughter than in exploring the troubled interior life of a recovering addict played by Seimetz who, like Fessenden, tends to have a terrible time of it on screen in “mumblegore” movies. The actress says she has no problem with the assorted torments her characters undergo in A Horrible Way to Die and You’re Next and, for that matter, Shane Carruth’s recent Upstream Color. “It’s so rare to see parts written for women where you actually do stuff and there are actual things happening [to you] as opposed to being this voice of reason for everyone,” she says. “But it is pretty funny. I called my mother because I had booked The Killing and I was like, ‘Oh, I booked another show.’ And she’s like, ‘Okay, what’s it called? I said, ‘It’s called The Killing.’ And she goes, ‘Jesus Christ.’” Seimeitz’s character spends much of the lengthy, climactic sequence of A Horrible Way to Die, hanging upside down, at the mercy of the movie’s coterie of killers. “That was pretty brutal,” says Wingard, of shooting the scene. “That was actually one of the most intense nights for me ever as director. Basically the last 15 minutes of the film was all done in one night. We ran out of time and so we ended up shooting for over like 24 hours straight and it was maddening. Everybody just felt completely insane. But I remember even thinking at the time, If we don’t just push through this right now, then we just aren’t supposed to be making movies. It was one of those very affirming kind of moments where we got through it and it wasn’t exactly perfect in the way that we had conceived it but we got it done, we sold it, and that got us a bigger movie.”

...

You’re Next premiered at the 2011 Toronto Film Festival and was bought by Lionsgate only to be shelved when the company acquired the company Summit — home of the Twilight movies — early in 2012. It took almost a year from its Toronto debut for the film to be given its release date. “It was a very complicated situation,” says Wingard. “But it’s all turned out great.” The company paid for further shooting on the film, including a sequence in which Fessenden’s character faced-off against one of the masked home invaders. “We did this one shot where he’s being tackled by a killer and it was very physical,” recalls Wingard. “We did it over 30 times and Larry just had the best attitude. He was just happy to f—ing to do it. Then he emailed us the next day telling us what a great time he had. I was like, ‘Thanks, I promise it was worth it — we used about take 24.’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, I knew we hit our stride around 22 or so…’” Fessenden remembers things slightly differently. “That’s not true, it was at least 45 times,” he laughs. “I’ll tell you, it was brutal. I was completely naked [except for] a towel and I had to be brutalized at the throat by a very sweet stuntman. Nevertheless, I kept ramming into his hand and my Adam’s apple hurt. In fact wanted to retitle the film Your Necks. Anyway, it was great fun. I hope he got what it wanted.”

Fessenden would also provide practical assistance to Amy Seimetz when the actress came to direct her movie, Sun Don’t Shine. “I had worked with him on Joe’s film Bitter Feast and he donated some money to Sun Don’t Shine,” she recalls. “What he’s doing for independent film is really inspiring to me. He’s just been incredibly giving to all of us with his time and mentorship.” Fessenden-the-producer has certainly been prolific over the past few years in terms of films he has helped shepherd to the screen, a list which includes Kelly Reichardt’s Michelle Williams-starring Wendy and Lucy, Jim Mickle’s apocalyptic vampire movie Stake Land, Rick Alverson’s The Comedy, a forthcoming documentary about Night of the Living Dead called Birth of the Living Dead, and Late Phases, a just-wrapped werewolf movie and the English language debut of much-tipped Argentinian director Adrian Garcia Bogliano. But Fessenden-the-auteur has had a leaner time of it lately. Indeed, since his 2006 eco-conscious horror movie The Last Winter he has directed just one movie, the recently released monster-fish movie, Beneath. “There’s no money for my kind of movie, a subtle approach to horror or a heartfelt terror-driven story that may or may not have enough gore or enough teenagers,” he says. “It’s very hard to get these films financed. The smart actors are scared of doing horror because it seems demeaning, and without a good actor you can’t pursue the kind of stories that I want to tell — which is smart, scary movies. But I live vicariously through the films I produce, and I get to see good work that I advocate for get made, and that’s always exciting.”

Fessenden also remains a busy actor whose credits over the past five years have included this summer’s Jug Face, Swanberg’s as-yet-unreleased drama All the Light In the Sky, and West’s 2009 horror film Cabin Fever 2, an ill-fated sequel to Eli Roth’s 2002 flesh-eating virus tale. West recalls shooting the film — which also featured an appearance from Swanberg– as a “great” experience but the director fell out badly with the film’s producers, which did not include Roth, in the editing process and departed the project. He now essentially disowns the film. “The way I describe it is, it’s like Dane Cook telling Seinfeld jokes,” says the director. “The material’s not so bad but the delivery is just messed up. I’m embarrassed to have my name on it.” West would recover his horror mojo on his next movie House of the Devil and is currently at work on an Eli Roth-produced film called The Sacrament about a Jonestown-style cult. The movie’s cast features three of his You’re Next costars: Joe Swanberg, AJ Bowen, and Amy Seimetz.

...

Fessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

JUNE 23 by BRIAN TRUITT

With a giant man-eating fish in tow, the maven of indie horror returns to the director's chair for the first time in six years with "Beneath."

STORY HIGHLIGHTS Larry Fessenden returns to the director's chair with the horror film 'Beneath' Fessenden started Glass Eye Pix in 1985 and it has helped careers of upstart filmmakers While 'Jaws' was seminal, 'Frankenstein' was what got Fessenden really into monster movies "I would not have told you a year ago I was going to make a movie about a giant fish. I can guarantee that much."

Nearly 40 years ago, that could have been Steven Spielberg talking about Jaws. Here, though, it's indie horror guru Larry Fessenden, who is just as much an American original.

Since the 1980s, he has been an actor, producer, director, mentor to other filmmakers and entrepreneur of the strange with his Glass Eye Pix production company, which has put out recent films such as Stake Land, Bitter Feast and The Innkeepers.

Fessenden blends the old school with the new in most everything he does, and always with fans in mind — the guy even put out a set of throwback Web radio shows called Tales From Beyond the Pale, with a second season coming this summer.

"Why not do audio programs in the age of YouTube and video!" Fessenden, 50, says with a laugh. "Part of it is just to re-engage the imagination of the kids and get them to enjoy stories in different mediums."

But back to that giant fish. A lover of the low budget, Fessenden returns to the director's chair for Beneath (in theaters and available on demand July 16, and on Chiller TV this fall), which features a group of recent high school graduates headed up to a lake to party and, in a leaking boat with an unfortunate lack of oars, find a man-eating, catfish-looking creature ready for a several-course meal.

It's Fessenden's first directorial effort since the 2007 environmental horror flick The Last Winter, and the latest in a career that started in the early 1980s.

"I've always wanted to direct, that's my priority," says Fessenden, who also has acted in films such as Bringing Out the Dead, Happy Accidents, Broken Flowers and even a modern-day adaptation of Hamlet with Ethan Hawke.

Fessenden talks with USA TODAY about the new film, the Jaws influence, what he doesn't like about today's horror and what favorite movie of his might polarize the viewership.

Q: What are you up to today?

A: I'm producing a movie in upstate New York called Late Phases, a werewolf movie. I think people are looking around for the next best thing but I tell you, werewolves have always had a special place in my heart.

Q: What's your favorite werewolf movie?

I had some fondness for the transformations even in the recent The Wolfman (2010), which was a fairly unsuccessful movie otherwise. And I grew up on Lon Cheney (in 1941's The Wolf Man). I love all the classics and more recently An American Werewolf in London. But I have loved the comic Werewolf by Night since I was a kid, and that's really the movie I want to make.

Q: What got you back in the director's chair for Beneath?

A: I've got several scripts I'm trying to raise money for, but I do make arty horror films and it's hard to engage the financiers. It's quite a dance to get movies made of the ilk I'm trying to do so I produce a lot in the meantime and always look around for material.

I went into Chiller to pitch a series of possible directors and low-budget projects and they pulled this out of the drawer. I said, "That one I would like to make," because I do love the giant fish in the water and I loved how contained this story was. I'm into pursuing horror with an allegorical quality, and this one had that.

Q: Was it always a large catfish hounding teenagers?

A: I had to do the sketches early on so that's what it was from the outset. As for the script, it was nondescript — the one thing in the script was that you could see it above the water with the oar stuck in it, so there are all those references to the shark element but obviously we weren't going to have a shark in fresh water.

Q: You can't talk about giant fish and not mention Jaws. Was that a seminal movie for you?

A: Everything about Jaws is deeply resonant to me. It's just in my DNA now. I was at the right age — I'd guess I was 12 or 13 (when it came out in 1975). I'd always liked monster movies and I'm old enough that I grew up on the old black-and-white movies. The effects were always a little awkward but you got into the vibe, everything from Godzilla to giant ants. When I saw Jaws, the genre seemed to grow up along with me with a more character-based story and this awesome creature.

I always laugh, though. Jaws' characters are deeply likable and in Beneath it's a different paradigm. I knew I'd never be making a movie that could gender the same sort of affection. It's funny to think of what makes a classic.

Q: Did it freak you when you were a kid or were you pretty used to horror at that time?

A: I really was obsessed with great white sharks. I wrote papers on them when I was little and there was a movie called Blue Water, White Death that was actually a documentary. I had seen that in a theater, and it blew my mind. I was deeply haunted by the idea of a great white shark and I used to go to Cape Cod, so I was always in boats.

It was a perfect storm for me to see this popular movie with great characters. I could tell even at that age that directing was unique. I had already seen Duel (in 1971) so I was already prepped to love Spielberg and his style, and there it was with a shark.

Q: Beneath also turns into a little bit of a Lord of the Flies situation with the kids as friendships go south very quickly. Is that what you wanted to explore, too, that the attacking fish isn't actually the worst thing in the movie?

A: If you've seen my films, usually nature is menacing but not really the bad guy, and here is a perfect example. This is really a movie about their complete inability to come up with either an ethical or a moral or even a practical survivor's decision. They're so entrenched in their petty grievances at each other.

To me, this is like the United States Senate — nobody gets along anymore to figure out how to come up with solutions, even when it is a matter of saving our (butt). "We're all in the same boat" is the cliché I would like to evoke here, and somehow humanity has lost the ability to work together to find solutions. You'll find that I speak loftily because I think that way, and I love to tell stories and use horror to expose the folly of our society and our goings-on.

Even more than the fish in Jaws, the fish in Beneath is not really a malevolent force. It's just doing what it does, which is eating anything it can find. It's actually not particularly menacing. And another thing is we chose to film in the daytime. In other words, there's nothing in the movie borrowing from the gothic clichés of darkness or mist. All of that is gone, so you're left asking the audience, so what's scary about this? The answer is clearly the (expletive) people can't get along. That's the horror.

Q: One of the kids is filming everything with his video camera. Is that analogous to teenage Larry Fessenden?

A: Not literally. Of course, in my day we had Super 8 cameras. I did make movies, including Jaws. If you go on IMDB, you'll see it under "Larry Fessenden." I wasn't trying to punk Spielberg or edge in on his glory, but I started making a little Super 8 movie of Jaws back in the day. So I was that kid.

Funnily enough, I was an actor on the stage in high school. I only learned about the camera in the mid-'70s and then I did start making a lot of Super 8 movies.

Q: You've also been in front of the camera over the years — your acting résumé is littered with the occasional cokehead, junkie, father, etc. Is there a favorite role in there?

A: Honestly it would have to be Habit, which is actually my own film (from 1995, about a man who is dragged into addiction by a seductive vampire). I only say that because it's the lead and I got to be naked, but look, it's also very autobiographical and I feel like there's some subtlety to the performance that you don't get when you walk onto a set for a day or two to play the maniac, which is the kind of roles I get. I'm fonder of the things where I had a little time to develop a character beyond "the freak."

But it's fun to do those and I do like it when people cast me in straighter roles. It's fun to show that side because I'm naturally associated with druggies and pimps and (Jack) Nicholson types. It's fun to surprise people.

Q: John Carpenter, George Romero and other genre legends are still making movies, but you have a whole new crop of filmmakers too. Right now, is horror a young man's game?

A: It's a good question. It is probably a young man's game in that there's a freshness and anger and an appreciation for the fast edits and gore that the youngsters like. In the one hand, horror moves forward with a new aesthetic, but the really deep themes should and can be explored by any artist.

I take horror very seriously as a way to express national anxieties. Some of the modern films, that's not the agenda — the agenda is to shock and titillate. That's something that kids can do well, but to me, a really great recent film is The Mist by Frank Darabont. He's sort of getting on and is an older, more mature director, but of course he's given us The Walking Dead.

Romero, you could say his zombie movies are getting tired but he's always got the deeper themes in there, and to me that's what resonates in the end is when the horror is actually about something.

Q: What really got you hook, line and sinker into horror when you were a youngster?

A: Well, that's where I'm going to just alienate half the viewership because my answer is Frankenstein. I'm talking about the real old films you saw on TV as a kid and I thought that was the most awesome concoction. I still stand by that. Karloff's Frankenstein (in 1931) is just an amazing piece of pop art.

More recently I was incredibly struck by The Night of The Living Dead and the hopelessness that that movie put forth. I've gone so far as to help make a whole movie (Year of the Living Dead) celebrating that film, so that's seminal, as well. And then you get into Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Shining, so there were always touchstones all along. Even The Omen was a great film when I was little to start seeing things in theaters and be blown away.

I liked B-movies as a kid, as well. I loved Them! and The Crawling Eye, In my generation, you didn't rent videos — you actually waited for these shows to show up on TV at 2 in the morning. You'd sneak out of the bedroom when your parents were asleep and watch these things, and they would freak you out.

The other thing that happened to me was I departed from horror. In the '70s I was a Scorsese fan. I would say One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest was an incredibly vital film to me because it's actually more about fighting authority and the other things that I'm engaged in as an artist and a person.

Q: What's the one thing about today's horror culture you would change?

A: It sounds self-serving, and let's just say that it is, I don't care. The fact is I'm sick to death of remakes when there are a lot of original scripts (to be made). You know what's wrong with remakes? It's that a good movie comes from its time and even the movies I don't favor like Saw, that felt right for its time.

Do you even remember these movies? What was The Thing remake? It doesn't feel like it comes form anywhere except the mind of a bean counter in Hollywood. And it's an insult to all the original material that the kids have ready to shoot that really springs from their lives now. Let's make a horror movie about Facebook. Go for it. Let's get on with this.

I actually don't mind the Paranormal Activity movies. They're cool. I'll tell you another thing about these movies is they force an audience to slow down. It's quite ironic that one of the biggest franchises is a celebration of a locked-off camera where nothing happens but a little weird sound. I'll take it.

Q: The Purge wasn't a remake and it really hit big recently, but Hollywood seemed bewildered by its success. To me, a hallmark of the horror genre has been original movies done on a low budget like Insidious that end up with a nice profit margin. Even with all the redos, horror seems to be the place with the most originality.

A: Horror comes from the fringe, and it used to truly come from the fringe, and now you have Hollywood embracing it occasionally. As you say, what are the movies that really stick out? It is a Paranormal, which was a completely unique film. So was Saw. So was Insidious — though (director James Wan) had a reputation by then, he still chose to make an original film.

I agree with you. The Purge has some problems but it's an original film. The irony is I am in You're Next, which is coming out in August, and that might be a more successful, similar people-with-masks-attacking-other-people movie. But we'll see.

The cool thing about horror is you can truly have expressionism in moviemaking, which has been drained out of the mainstream. If you watch old '70s movies, the editing is far bolder than what you see now. With superhero movies and all of this, it's all gotten very regular. CGI has also leveled the component of wacky imagination because you just create something that looks very real on a computer whereas in the old days you had to use the medium very creatively. Horror still does that to some degree because it's trying to take you into a dream state or disorient you. It really uses the language of cinema to disorient and freak out.

But I'm not a huge fan of gore. I loved gore when it was actually shocking and when it first made its appearance, and I find it redundant. To remake Evil Dead with just more gore is not the agenda, folks.

Q: You started Glass Eye Pix in 1985. Was the goal just to create your own thing, maybe even anything at that point as a youngster?

A: That's exactly what it was. Honestly, I was looking for something to copyright a movie I made and I came up with this idea of Glass Eye Pix. A friend had given me a glass eye. "Pix" came from Yankee Doodle Dandy — I was a huge James Cagney fan. The spelling of pix is from the old Variety speak. You used to talk in tongues when you read Variety headlines.

I started the company and then would make videos with performance artists in the '80s and then started doing my own films. It started turning into a little shop for up-and-coming filmmakers really in the 2000s when I started helping other filmmakers get their low-budget movies started. I was sick of hearing about format and people waiting to raise money, and I was a big believer in "Let's shoot video then if we can't raise money for film." I got a couple of kids inspired like Ti West and it went from there.

Q: Do you have plans to do more projects like Tales From Beyond the Pale aside from the indie films?

A: I love the genre and I grew up in those days where even the movie poster was an essential component to the experience. There were no making-ofs, no video rentals — you had the Famous Monsters of Filmland magazines that showed you stills from movies. Sometimes you never saw the movie but the still would live in your imagination.

I'm obsessed with creating a little world where the posters matter, where there's a comic spinoff, where you tell the story in different ways. It also speaks to the Rashomon life that we all lead where there are different versions of the same story and they have different reverberations.

When we made Stake Land, I had several directors make webisodes that connected to the feature, and I feel like it just enriches the world. On the one hand, I feel like a man out of step with the current culture, but actually this is exactly what transmedia is and it's what everybody does and something I've been doing since the 1990s. It's fun to realize that you actually do have your finger on a certain pulse. That's why there are so many incarnations and spinoffs even in my own little, very low-budget world.

I'm always imagining that there's fan out there who's getting it. That's the real motivator. I think of what I do is for that fan, that collector, who is actually putting the pieces together, That makes it all fun to imagine somebody going, "Oh, that's so cool they did this!"

(Sunday Geekersation is a weekly series of Q&As featuring luminaries, mainstays and newcomers of geek culture discussing their projects, influences and pop culture.)

Fessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

Interview by Danny Trudell (from 2009; published 2012)

A number of years ago, I rented the movie Wendigo by Larry Fessenden, mostly by chance. I was stunned at how beautiful it was – the entire movie was astounding from start to finish. I would watch and re-watch this movie for years. Loving Wendigo made me want to know more about the director and the other projects he had been involved in. After some research, I found that not only did I love the movies Larry was making, but I would draw parallels between his ethos and that of the punk rock/hardcore scene I grew up in. Larry is an uncompromising filmmaker who exemplifies the do it yourself attitude. He eschews the Hollywood model for how films are made, and makes movies his way, without compromise. He doesn’t see budget restraints as a hurdle or stumbling block, but rather as a chance to more creatively take the viewer where he wants them to go. Larry works outside of the mainstream, while making movies that are better written, better looking and more engaging than 90% of the crap playing at your local theatre. I was thrilled when Larry granted me this short interview, allowing me a peek into the mind that has conceived so many films I love.

How old were you when you realized that making movies and acting was something you wanted to do with your life?

I was pretty young. I remember in the third grade play I played the dragon that fought Perseus. It was a tiny role, I basically walked on and roared and then got killed, but the tumble off the stage I took was the talk of the school for days. I never got the leading man roles, but I made the most of character parts. I did play Marc Anthony in Julius Caesar in 8th grade, but by then I’d already made some movies and was very into the performing arts. In those days (the 70’s) it wasn’t clear that you could actually aspire to grow up and be a film maker. I came from a conventional family and we just didn’t think that way. Hard for kids to understand now.

How did you get your start in filmmaking?

I helped my brother’s friend make an elaborate animated movie with all my GI Joes when I was very young, like 9 or so. Then when I was 12 I used the school super 8 movie camera to make a version of DR. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but none of it registered, and I was mostly into acting in plays until I got a super 8 camera of my own and that’s when I discovered that the camera was the story-teller in movie making. That is when I moved from acting to film making.

I know a lot of people absorbed in mainstream movies are looking simply to escape and be entertained, and though I do enjoy your movies as entertainment, there is also an honest communication in your films. How do you find the balance between your artistic vision, entertainment and the message you are conveying?

I don’t know if I have found the balance. All I know is it takes so long to make a movie that, for me, it has to be about something that sustains my interest and something that actually matters. But I grew up on horror and main-stream films, so the movies that influence my stories are very genre-based. I think of film as a medium of communication. I am trying to convey as directly and honestly as I can the sensations I have being alive, afraid, pissed off, sexed up, confused, vulnerable and awed by the world. I want to convey that with candor and skill. That is a huge personal undertaking. I don’t know how else to approach the medium.

Do you ever worry about what the audience will think, or do you simply make what you think is right and hope the audience is open to what you are bringing?

I worry about the audience in a very particular way: I wonder about each choice I make in terms of how it will psychologically affect the audience. This is the way in which Hitchcock talks about audiences. Nowadays, there is a new concern: is the audience too jaded to even accept the offerings one is making? There is so much media and so many opinions about it that these concerns creep into the equation. But ultimately, one must find a passion for the material that blinds one to all these concerns.

A lot of people would discard horror movies as garbage, but you tackle real life issues with your movies. What is it that made you pick horror as your vehicle to express these ideas and feelings?

Nowadays, horror movies are grotesque gore spectacles, and I wouldn’t really defend the genre myself. But everyone on earth deals with fear, and is to some degree motivated by fear. And that is what the horror film can explore. I did not pick horror. Horror picked me.

I read an interview with you in the past where you talked about how you really make your movies three times – can you explain what you mean, and what your favorite part of the process is?

Well, it’s not an original idea, I lifted it from someone, but it is a simple truth: when you write a film, it has a life on the page and its own integrity. When you film the script, everything changes — the actors bring unexpected readings and nuance to their roles, and the weather and time constraints and money and sets and so on — all of this alters to some degree the script. And then any filmmaker worth their salt knows that when you edit, you must respond to the material that was actually shot and remake your film a third time. That’s the one that counts.

You state clearly that movies do not have to cost a lot; do you feel the limited budget you have worked with stimulates a more creative output than if you were handed all the money in the world to create your films? Also just to show people what can be accomplished with sheer passion and drive, would you tell us the lowest budget you have ever worked with on your movies?

I don’t want to romanticize having no money to make a film, because there are very real considerations such as feeding, housing and paying crew members, and there are things like special effects, locations and post production that all cost money. However, I do equate low budgets with more creative freedom, and more physical mobility, and yes, I enjoy the challenge of solving story and technical problems with ingenuity rather than money. I made a movie in 1985 called EXPERIENCED MOVERS for $10,000, my own film HABIT was shot for $60,000 in 1994, and some of the films I’ve produced, like TRIGGER MAN and AUTOMATONS, cost around $30,000 each. My intention in speaking about low budgets is to inspire would-be filmmakers to go out and make a movie, rather than wait for a budget to materialize that might never come. Learn the craft; it can be done with a flip camera.

You started your production company Glass Eye Pix in 1985, and here you are, still working and growing in 2009 – did you expect things to take off for you on the level that it has, and to have survived as a company for so long?

I don’t know what I expected, but I did hope to be a working filmmaker by now, making films like the ones I loved. I doubt I expected to produce as much or have a band of brothers that makes movies together, but that’s what’s happened and it makes sense to me.

I know in this day and age, people often feel things like making movies, releasing music or communicating their ideas are out of reach of the common person. What drove you to start your own production company and make your own movies?

Now more than ever, you can make art and have it seen by the whole world through the internet and, thankfully, there are still supportive networks of coffee shops and clubs on every corner of the planet, so being an artist is possible. Making money at it, making a living, there is no guarantee for that, but if it is what you love, what you must do, then there are more opportunities now than ever to get your voice heard. Real financing is very tricky right now, so it takes a certain ingenuity and drive to get something produced in this economic climate.

One of the things I loved is reading about was what a sense of community and family you have established with Glass Eye Pix. Can you tell me a little about the importance of the collaborative effort in making your movies, and giving a leg up to filmmakers you see coming up?

I always say I am a bit of a lone wolf creatively – I am quite shy and secretive about my own work. But what I believe in is the artistic collective, where a group of like-minded artists form an identity that gives strength against the corporate voice. A bunch of rag-tag artists with a shared vision can establish an identity that resonates with the public, and a company name can become a reliable brand. When I was growing up, as a fan of movies, I knew that each studio had a style of movie they were associated with: Universal made horror; Warners made gangster pictures with social realism, MGM musicals and spectacle and so on. Same with the record labels of the 60’s and 70’s. I always enjoyed learning of how different artists were connected to each other, and imagining how they related: Lou Reed and Andy Warhol, or how Coppola and Lucas helped each other. There is a comfort in knowing these giants of the arts had rivalries, loyalties, and insecurities like the rest of us, and that you can’t do it alone.

I know that your concern for environmental and animal rights issues have manifested themselves directly into the subjects of your movies, what brought these issues to light for you?

Some time in 1986, my friend Alex Wolf gave me a copy of Silent Spring. He must have known it would affect me. That, and subsequent environmental literature, has had a profound and lasting effect on me: I gave up eating red meat and birds in ‘87, and have generally been plagued by my outrage over the misuse of resources and the hubris of humanity. This outlook has literally poisoned my outlook on life, and it has become the source of my horror stories, not because I am a propagandist, but because I am so hurt and outraged by these conditions.

As an actor you have starred in movies by Martin Scorsese, Neal Jordan, Jim Jarmusch and Steve Buscemi -a pretty impressive group of filmmakers. Did working on these projects help you or teach you anything that translated to how you work on your own movies?

These associations have made me very grateful and humbled, and yes, you learn something on every project, observing how each director approaches the process. I learned a great deal acting in Kelly Reichardt’s film RIVER OF GRASS years ago, because I’d made a bigger-budgeted film, and had lost touch with what I liked about filmmaking. RIVER OF GRASS inspired me to make HABIT for very little money. What I loved about Scorsese is how he could see moving shots intercut in his mind, I could watch him build the movie right there on set. It has been a great privilege working so close to these remarkable auteurs, seeing how each one builds a scene and the confidence that success has brought them.

Would you name a few directors that influenced you, and subsequently could you name a few directors you see coming up that you are excited about?

I am highly influenced by Hitchcock, I am inspired by Scorsese, Polanski, Kubrick, Kurosawa. Recently, I was excited by Neill Blomkamp’s debut film DISTRICT 9. And of course, I am inspired by my collaborators and the directors whose work I have produced.

Finally, if you had all the money in the world to work with, would it change at all how you make your movies?

It would make a difference to be able to plan when to go into production based on the weather, the time of year. You could hire the actors you wanted and generally have the creative freedom that time affords. But there is no point in thinking that way, because no one has enough money, your budget expands out of your grasp at every level of filmmaking, and ultimately filmmaking is about solving problems and working with and defying your limitations.

CVLT Nation would like to thank Danny Trudell for letting us publish his rad interview with Larry Fessenden!

Fessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

Larry Fessenden is a prolific figure in the world of horror. As a director, he has made only five full-length films, but he has produced and starred in over 40 other features. As actor and producer, Fessenden’s films range from B-movies, best watched after several drinks on Halloween night, to cult classics in the making by up-and-coming directors. However, as an auteur filmmaker (he produces, writes and stars in most of the films he directs) he has brought a refreshing new voice to a genre that seems too often unwilling to experiment – ironic for a type of storytelling that is all about the fear of the unknown.

At this year’s FrightFest, he spoke on stage as part of a panel of his peers (Ti West, Lucky McKee, Adam Green, Joe Lynch and Andrew van den Houten), who are almost exclusively directors of slasher movies and ‘torture porn’, and, with the exception of McKee, have done little to innovate. Hilariously, these directors had the arrogance to complain about big-budget horror remakes in recent years being helmed by ‘unknowns’ – second-unit directors and editors of Hollywood schlock. But the truth is, their own output is barely known outside of the cultish clan of aficionados with a high tolerance for the drivel often found at horror festivals.

Fessenden’s work is also little known outside of the pages of Fangoria or independent video shops, but in his four horror films (his 1985 Experienced Movers has rarely been seen since its year of production) and one TV episode, he has established himself as a terrific filmmaker. First was a thoughtful trilogy that commented on the classic tropes of horror films – Frankenstein in No Telling (or The Frankenstein Complex, 1991), vampires in Habit (1995) and werewolves in Wendigo (2001) – followed by The Last Winter (2006) and Fear Itself: Skin and Bones (2008), in which he further explored the myth of the Wendigo.

In Native North American folklore, the Wendigo is a kind of cannibalistic spirit with a shape-shifting exterior. In Fessenden’s films, the Wendigo’s appearance changes, depending on who is telling the narrative. In Wendigo, it first appears (or rather, doesn’t appear) when the members of a family who survive a car crash all encounter different aspects of an animalistic shape, one part sticks rustling in the wind and one part fur-covered Arctic predator. Here, the Wendigo has some kind of amorphous role in protecting its environment, but the link between the creature and the land is made more explicit in The Last Winter. As a multinational company starts drilling in the Arctic tundra, the humans who have braved the lethal environment encounter the spirit: first as a flock of birds, ready to peck out the eyes of anyone crazed enough to stay outside to the point of hypothermia, then as madness that drives the men into the cold, then as an enormous shadowy figure made of smoke that stalks the land at night. Finally it appears as a flock once more: dark, velociraptor-style predators gorging themselves on the human remains. In The Last Winter, Fassenden presents the monster as a monitor and destroyer of the men who encroach on its territory or endanger the planet. In his TV episode Fear Itself, Fessenden reveals it to be the animal within, as a character in the show transforms into the Wendigo.

Fessenden is interested in the ambiguity of horror and of storytelling, and in unreliable narrators. Fessenden challenges every aspect of mankind, from our position at the top of the food chain, to being subservient to an eco-system we try to master, to the unreliable perception of the environment itself. Science fiction wouldn’t be a challenging enough genre for this kind of storytelling – although the director flirts with it in No Telling when a mad scientist experiments on the animals in his care. Fessenden wants to disrupt, to unsettle and to disturb, while keeping an ecological leitmotif in all of his horror films, except Habit (and even then, perhaps, the transformation of man into vampire is a type of evolution).

Since 2001 his films have been beautifully shot and thoughtfully directed, evolving from his more underground, ultra-low-budget roots to slick verisimilitude, which seems comparable to the work of the Coen Brothers (if they only worked in horror). The only flaw in the director’s tales is his unwillingness to provide his films with a definitive or satisfying ending – but if horror is to disturb and unsettle, perhaps one should leave the cinema with the sense of a drama left unresolved. Certainly with Fessenden, the journey to a final door left ajar is always one worth taking.

I spoke to Larry Fessenden immediately after the panel discussion on modern horror at 2011′s August FrightFest.

Alex Fitch: You spoke eloquently on stage about how you had a love of classic horror films as you were growing up, of RKO films like King Kong, and then in the 1960s, films like Night of the Living Dead. But, as well as an interest in those classic horror tropes, something that’s very prevalent in your movies is your anger about how man is destroying our environment. What sort of experiences in your formative years created that anger?

Larry Fessenden: I’m not impressed with people who put on airs, and I think the whole of humanity has that element. I had a passion for thoughtful and eccentric people – I went to a great school when I was young, and I thought that was the way of the world. Then when I went out into the real world, I saw that many people were faking it, and were un-genuine, and would call on the name of a religion in a false way. So it’s an anti-authoritarian thing. I also grew up going to Cape Cod and liking nature, respecting it. I’m not an outdoors man, I just believe in respect for your elders, and there’s nothing older than the Earth. Although some in America would question that, too.

In films like No Telling, humanity has manipulated evolution for our own survival. When it comes to presenting that on film, horror is a very good way of doing it, but how do you avoid making it just an issue movie?

Well, some people would feel that I do preach – at least in No Telling, I think things got carried away. There’s a central scene where they’re arguing at a dinner table, and the point I’m making in that scene, which the casual viewer sees as preachy, is how we can’t communicate. You go to parties and people do talk about politics, and you walk away and you realise you can’t change people’s minds. I find that fascinating. So, in a way, I try to have movies where there’s some dialogue about a situation. But then there’s the reality that you’re showing cinematically, and then the one that trumps it – because reality will trump all this conversation. You can say something like global warming is not true, but the fact is, there’s going to come a time when it simply is true and then you have to deal with that.

That basic betrayal of our potential as a species and as individuals is really what drives me. Habit is about how that guy cannot rise above his alcoholism, cannot find his better self, and that’s the tragedy of humanity, I think. That’s why my movies are personal, even though they have this political veneer. If you deal with the environment, people will be defensive, because in our heart of hearts, we all know that we are part of the problem, which I also find interesting and horrific. It’s really what I love about horror – it’s the truth-teller of the genres. I don’t want to make movies that preach about politics, I find that uninteresting, so I have a monster come along, and that vindicates nature!

I suppose the supreme example of that is Wendigo, because it’s very much about the myth of a creature on whose description no one can agree.

Exactly.

It seems very brave of you, that unlike a lot of filmmakers, you will show that it looks different to many people. To the audience that can be frustrating, but there’s an honesty there.

I believe that if you show the monster in different ways, you’re getting at the essence of another theme that interests me, which is the subjective nature of reality. I mean, to one character in Habit, his girlfriend’s a vampire; to his friends, she’s an interloper, taking away his attentions from their party life; and then in the end, there’s a very subtle thing where you realise that both stories are true. He’s either fallen out of the window alone, or he’s fallen out with her. I love this slippery reality. I believe in a very deliberate ambiguity in storytelling because that is how life is. It’s appalling, sometimes, when you talk to someone and realise they hold a different view, and they’re absolutely coming from a genuine place. You realise it’s hard to connect, and it has to do with their upbringing, and every subtle thing that creates a human personality is in play – I like to show that in movies. I think the nature of horror is that it allows you to delve into issues of split personalities, of unreliable narrators and untrue, slippery reality.

The ambiguity of horror films seems to be an antidote to the encroaching apocalypse presented constantly in the news. You spoke on stage about the August riots on the streets of London – but if society is going to collapse, maybe it’s these communal myths that can bring us together again?

Well, that’s also my business. In my films, I’m trying to show not which myth to follow, but how important myths are to give us meaning – because otherwise you’re left with a very bald, desperate reality that is amoral. So I celebrate, and I want people to acknowledge, that if you are clinging to mythologies and your world view is formed for a reason, then you can at least get a window into someone else’s world, and that gives you some hope. I really think the pinnacle would be to make a film that created a new paradigm for people to get behind, and that’s why I’m trying to suggest that could be nature in some way. It’s funny, most people think that my movies are about nature getting revenge and being threatening, but I’m saying: ‘Have awe. Have respect.’ I’m not really saying it’s a baddie. But you realise you can be easily misinterpreted when you’re dealing with something so primal as our relationship to the rest of the world. That’s why I’m not interested in The Exorcist type of film, because it’s dealing with God and the Devil, and I’m like, ‘Let’s stop talking about good and evil and let’s look at this whole other paradigm.’ So, while I’m not going to single-handedly save the world, that is my preoccupation, to sort of put forth a new way of looking at our reality, and if we could agree on that, then maybe we could get to this business of saving ourselves!

Interview by Alex Fitch

Fessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

A Kingmaker in the Realm of Cheapie Horror

By ERIC KOHN

LARRY FESSENDEN knew something was wrong with “Stake Land,” a bleak horror movie about the survivors of a vampire outbreak, before the filming even began. Mr. Fessenden, a producer of “Stake Land” through his Glass Eye Pix company, worried that an early outline for the movie lacked emotion and resembled a cold, action-driven blockbuster, the kind with a histrionic soundtrack. So he invited the movie’s young director, Jim Mickle, out for a drink.

“Give this a heart,” Mr. Mickle said Mr. Fessenden told him. “We didn’t hire you to make ‘Terminator 5.’ Go make the only movie you can make.” The result, an evocative post-apocalyptic tale that emphasizes feelings of isolation rather than bloodshed, won an audience award at the Toronto International Film Festival in the fall and has garnered unlikely comparisons to the work of the director Terrence Malick.

Mr. Mickle, 31, gives much of the credit for how the film turned out to Mr. Fessenden. “Larry could see that I was trying to force it into something that it wasn’t,” he said recently.

Mr. Fessenden, 48, a staple of the New York underground scene as a writer, director, producer and actor, says his advice about “Stake Land” was merely practical. “It’s a road movie and a western,” he said recently over coffee in Union Square. “It should never be horror for horror’s sake.”

A scraggly-haired man easily recognizable by a missing front tooth, Mr. Fessenden has produced around a dozen micro-budgeted movies in half as many years. He advocates a form of eerie storytelling that he says Hollywood abandoned long ago in favor of blunt scare tactics. “The horror should creep in,” he said. “That’s how it happens in real life.”

When advising Mr. Mickle, Mr. Fessenden spoke from experience. He has also directed a vampire movie, “Habit” (1995), an allegorical story in which he starred as an East Village resident inadvertently dating a fanged bohemian.

Mr. Fessenden has shared his filmmaking secrets with like-minded directors for decades. “He’s really great at being able to not impose what he would do, but he can figure out your aesthetic and talk to you about it,” said Kelly Reichardt (“Meek’s Cutoff”), whose 1994 debut feature, “River of Grass,” starred Mr. Fessenden.

But since 2004, when the filmmaker James Felix McKenney convinced him to create a low-budget production arm of Glass Eye Pix called ScareFlix to produce Mr. McKenney’s ghost story “The Off Season,” he has formalized that mentor status and gained a reputation as a modern-day Roger Corman.

“Larry validated us by thinking we were talented,” said the director Ti West, whose first feature, “The Roost,” was among ScareFlix’s initial offerings and brought Mr. West a cult following of his own. “The movies have done well, but mainly I really enjoy having Larry as a part of my life.”

Mr. Fessenden’s varied themes as a director have included addiction and the gradual destruction of the human race. Among his influences are Universal monster movies from the 1930s and ’40s and the New Hollywood cinema of the ’70s, and his films often reflect his ecological concerns. (He runs a conservation awareness Web site called Running Out of Road. “We’ve lost our great potential to be a cool species,” he said of global warming. “The horror that really interests me is this horror of self-betrayal.”)

Mr. Fessenden speaks about his mission to foster emerging horror filmmakers with the same ferocity he brings to environmentalism. “I absolutely insist the marketplace make room for these types of movies,” he said, lauding films like the original “Night of the Living Dead” and “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” for their critiques of excessive human behavior. “If not, we’ve lost our souls. These are personal films, not cookie-cutter filmmaking for a brain-dead mall culture.”

He reserves particular disdain for the “Saw” franchise. “It’s just exploitation and titillation for kids,” he said. “I don’t buy it. It’s not about anything.”

Despite that anti-consumerist streak, Mr. Fessenden and his team are successful businessmen, most recently establishing a relationship with the distributor Dark Sky Films. After the two companies produced Mr. West’s satanic thriller “The House of the Devil” in 2009, they announced a three-movie slate that included “Stake Land.” Budgeted at just $625,000, it was the most expensive of the lot. That tight rein on costs has kept investors satisfied. “It’s nice to see this family of people Larry has put together,” said Greg Newman, executive vice president of MPI Media Group, which owns Dark Sky. “They’ve been so consistent. I think he’s doing something fairly unique by filling a niche market for the elevated, smart genre film.”

Still, most of the Glass Eye directors say they would like to try bigger projects. “We’ve gotten a little older and slightly exhausted by low budgets,” Mr. West said. “But maybe the frustration of waiting for the next thing will spawn more smaller movies.”

Mr. Fessenden can relate. “I’m very schizophrenic about it all,” he said. “I’m pleased to be doing this with the young fellers, but I also need to get back on track as a director.”

A few years ago, he tried to do just that. Handpicked by Guillermo Del Toro in 2007 to write and direct an American remake of the Spanish horror film “The Orphanage” for New Line Cinema, Mr. Fessenden immersed himself in the project, jetting off during the shooting of “Stake Land” to meet with potential cast members.

By late 2009, however, he was dropped from the project. “My clock ran out,” Mr. Fessenden said with a hint of anger. “The studio decided that, because of my unproven status, they couldn’t cast it.”

Mr. Fessenden, however, has plenty to keep him busy. In addition to the numerous Glass Eye Pix movies, he enlisted 10 filmmakers and writers to produce “Tales From the Beyond the Pale,” audio recordings of 10 short stories in the mold of old radio serials, due out this summer on CD and iTunes. And he has been talking to a distributor about releasing a restored version of “Habit” and re-releasing his overlooked debut, the 1991 ecological Frankenstein shocker “No Telling.”

On a recent evening, Mr. Fessenden participated in a public discussion about his career at a small theater on the Lower East Side. Before it began, he held court at the bar. “I really believe in the no-budget model,” he said to a fan, his voice rising above the crowd. “My life ambition is to give a million dollars to someone like Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese and have them return to their roots.” He paused to let the idea settle. “This is what I want for Glass Eye Pix,” he said.

Fessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

Thursday October 21, 2010

As a kid, Larry Fessenden didn't idolize all-star athletes or astronauts. His heroes were Frankenstein and the Wolfman.

"I'm of a generation that watched movies on TV," the New York-born filmmaker said. "I loved the outsiderness of the monsters. Very often, you had an affection for the creatures."

These extraordinary beings weren't disposable bogeymen, but occasions of uncanny wonder. "Some jerk stole horror and turned it into meaning slasher movies. When I was little, horror meant great stories of mythic proportions, about playing God and science and nature and werewolves and drinking potions and giant tentacled creatures coming out of the ocean. That's what I wanted to see."

Since 1985, when the East Village resident founded the independent film studio Glass Eye Pix, those have been the kind of films Mr. Fessenden has made—although conceived with a contemporary, urban perspective. Whether shooting his own efforts or producing the work of other filmmakers under the company's banner, Mr. Fessenden, 47, has shepherded more than 20 movies to the screen, some with budgets as low as $20,000. The body of work will be celebrated in a two-week retrospective, "Larry Fessenden: 25 Years of Glass Eye Pix," opening Friday at reRun Gastropub Theater in DUMBO.

The program features several of Mr. Fessenden's unpredictable twists on genre—vampires in "Habit," weird science in "No Telling," Native American lore in "Wendigo" and "The Last Winter"—as well as sharp-witted turns by directors Ti West, Glenn McQuaid, Graham Reznick and James McKenney. As a producer, Mr. Fessenden said, he's also been heavily influenced by the social realism of American films of the 1970s, when films like "Mean Streets," "Straw Dogs," "The French Connection" and "Dog Day Afternoon" embraced complex situations and characters informed by the tensions of the post-Vietnam era.

"All of it comes from a fairly unique, auteur-driven place," he said of the films he now champions. "They're not opportunistic cabin-in-the-woods films where you set out to make a horror film. I feel they're usually driven by someone's inner demon. They very often have a sense of humanity to them. They're really not pure exploitation films. They're exploring the dark side of life as it exists."

At reRun, the series will skew toward Glass Eye Pix's genre efforts, excluding titles such as Kelly Reichardt's "Wendy and Lucy," on which Mr. Fessenden was a producer, in favor of more Halloween-appropriate fare. But as Mr. Fessenden stresses often, the formula elements in each film are always secondary to original yarn spinning. "Someone like Ti West ("The House of the Devil"), he's telling the tale of a babysitter-Satanic cult situation gone awry. But it doesn't telegraph the horror. It's very much how it would unfold. I'm looking for genuine voices as opposed to people who are trying to use genre to advance their careers."

Mr. West, whose films "The Roost, "Trigger Man" and "The House of the Devil" will be screened, has become one of the most successful members of the Glass Eye crew. He credits Mr. Fessenden's laid-back approach with fostering a creative environment for emerging filmmakers. "Larry doesn't have this ego problem," he said. "In fact, he places an exceptional amount of trust in his directors and their collaborators."

Jim Mickle, a young filmmaker whose post-apocalyptic "Stake Land" will open next year, suggested that Mr. Fessenden has remained in touch with youthful enthusiasms that most adults set aside. "Larry is like a little kid who hasn't fully grown up," he said. "I mean that in the best possible way. His love of Hitchcock and Polanski is equal to his love for 'The Karate Kid' and the Wolfman. He wears his affections proudly."

Perhaps Mr. Fessenden's best-known attribute is his habit of getting killed in mainstream Hollywood movies. His shaggy hair, jutting forehead and absent front tooth—knocked out by a gang of Brooklyn street toughs in 1984 when he came to the defense of his then-girlfriend—frequently gets him cast as a creep du jour. Jodie Foster iced him in "The Brave One," although in Jim Jarmusch's "Broken Flowers," he plays a biker who punches Bill Murray in the face. Win some, lose some.

"I've lost track of how many times I've been killed," said Mr. Fessenden, who has been shot, ice-picked, defenestrated, mauled by rat zombies and chainsawed, among other fates. He assembled a short video of the various death scenes called "The Assassination of Larry Fessenden," and will show it on Halloween. "I think it's nine or 10. I was telling ["The Last Winter" actor] James LeGros this, very proudly, and he told me he'd been murdered 18 times. The difference is, he has real roles. I come on and I get murdered."

linkFessenden bio | "Someone to Watch Award" | top

Three Films By Larry Fessenden / 22nd March 2010

Three Films By Larry Fessenden

As driven as Roger Corman; as authentic as John Cassavetes; as subversive, bold and transgressive as Stuart Gordon. In the early 1990s rush of independent film revelry, while the world was rightly fawning over the collective visions of a new band(e) of vibrant, cine-smart filmmakers -- among their number Allison Anders, Whit Stillman, Richard Linklater and, of course, Quentin Tarantino -- one name was lost in furore over the free ideals, cultured formalism and rampant creative frivolity of this post-Soderbergh Sundance set. The name was Larry Fessenden.

It would be disingenuous to ever imagine that he would *really* be included on such a striking role-call. Yet looking back at the down-and-dirty-pictures epoch with eyes that are two decades older, it’s strange that Fessenden’s dramatically bold, genuinely unkempt mindset wasn’t at least latched upon with the same fervour that champions of the indie movement afforded less-resilient talents like Nick Gomez or Alexandre Rockwell.

Three pictures in particular, a trio that would become Fessenden’s Trilogy Of Terror, sum up his slightly feverish outlook on the world. It’s a world stuck between twin pillars: ennui at the emotional upheavals of simply living in contemporary society; and a basic fear of it. The world is a deeply unsettling place and those who inhabit it make it so.

I wrote in my Underrated Film of the 21st Century column in July of last year about the third of these films, WENDIGO. Released in 2001, WENDIGO was the final part in the Trilogy Of Terror. These were a series of otherwise unrelated films that took on horror archetypes, reinventing them in a smart, sharp fashion that bridged their literary pasts with their more prevalent (and over-exposed) cinematic present.

WENDIGO was, to all intents and purposes, his Golem picture wherein a family in the embryonic stages of marital discontent are terrorised by something from within the woods in which they are vacationing. The more unnerving intimation is that what’s terrorising them is perhaps made from those woods.

WENDIGO enveloped the essential primal fear which the enduring Jewish anthropomorphic talisman possessed, but from a distinctly pagan perspective. This tree-demon seems generated by the awesome power of nature itself; the rural beasts of nature striking back at the urban(e) beasts from the city.

Deconstructing the iconoclasm of fear, Fessenden asks what it takes for an icon, be it beast or bogeyman, to survive in a contemporary age where everything is accessible, where knowledge is a mouse-click away and where fear and superstition have been usurped by reason and rationale born of technology and science. Out in the wintery wild woods, none of the trappings of modern civilisation can be relied upon to explain the uncanny occurrences that terrorise our heroes. The journey that follows, complete with a terrific Quay Brothers/Jan Svankmeyer-style stop-motion monster, is as neat and nihilistic as anything from the glory days of Val Lewton’s tenure at RKO.

WENDIGO was a technically polished production, the most mainstream yet from the remarkably industrious Fessenden and his Glass Eye Pix production outfit and a move away from the feel of his earlier pictures. These initial features, after a series of shorts, may have been more rough hewn but they were no less invigorating, imaginative or fiercely intelligent, traits which more visible low budget horror pictures of the early 90s were more willing to spurn in favour of gore gags, T&A and ever more quip-laden post-modernism (taking more obvious cues from that previously mentioned auspicious list of cine-savvy filmmakers from which Fessenden was noticeably absent).

His first feature was 1991’s NO TELLING. Ostensibly a retelling of FRANKENSTEIN (by way of Herbert West) it sees a modern couple, Lillian and Geoffrey, spurn the lights of the city for the quiet life in the country. She’s a free-spirited artist; he’s a research scientist with some deeply divided ethics on the treatment of animals in the quest for an elusive and lucrative grant. Muddying the waters with dramatic tension is a nefarious conglomerate raping both the land and the health of local farmers -- forerunning such big budget portraits of scandalous corporate misdemeanour as A CIVIL ACTION and THE RAINMAKER. Lillian befriends activist and neighbour, Alex, whose job it is to monitor and take action against the hazardous chemical influx on behalf of his fellow citizens. (And, like a loveably hippy dippy liberal, promote organic farming! This was before it became hip to do that very thing, I suppose.)

Naturally the mad doctor’s hubristic quest gets the better of him and before the credits roll, more than a little blood has been spilled in the fight to rectify the natural order of things.

If it sounds didactic for a horror film, well, to some extent that’s true. Somewhat crude but imaginatively shot, it’s a picture of its time -- the early 90s when such environmental concerns were at an apex of scientific advancement and popular activism -- but also a picture of a very old fashioned persuasion.

Like another low-budget maven I’ve championed at Frightfest, Jeff Lieberman, Fessenden is a cultivated genre fan and nowhere is this more evident than in NO TELLING, which owes as much to the stern-faced sci-fi pictures of the 1960s and 1970s as it does to the more apparent mad scientists beloved of gothic literature.

Somewhere between 1950s sci fi of THEM and the following decades’ PHASE IV and THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, sci-fi/horror pictures became less hysterical and more gravely austere. As society came to terms with the 20th century’s fantastical technological progressions, things that were once the stuff of crazy, b-movie nightmares were an empirical reality. The 20th century’s greatest irony is surely never forgotten; that as advances of modern science brought about wonders of hi-tech communication, healthcare, and commerce, the Faustian pact meant there was an exponential descent into chaos, suspicion and conspiracy as we irrevocably lost our collective innocence. As the Cold War descended and we progressed past Korea, past the Bay Of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis, past Vietnam and Nixon, society realised that just because a government was in power, they and their associates weren’t necessarily doing things in the best interests of the people. They weren’t to be trusted. Nowhere was this paranoia more viscerally exploited than in genre film.

NO TELLING, though a contained, intimate shocker, honours this inquisitive, intelligent fiction of mistrust in a quietly compelling manner.

Perhaps the most interesting of Fessenden’s Trilogy Of Terror is the least traditionally “horror”. 1996’s HABIT is a modern day retelling (and regendering) of the basic Dracula story in which Sam, an out of work actor and bar manager in the bustling artistic haven of Greenwich Village, is seduced by a predatory female partygoer. It is written, directed and edited by and stars Larry Fessenden himself.