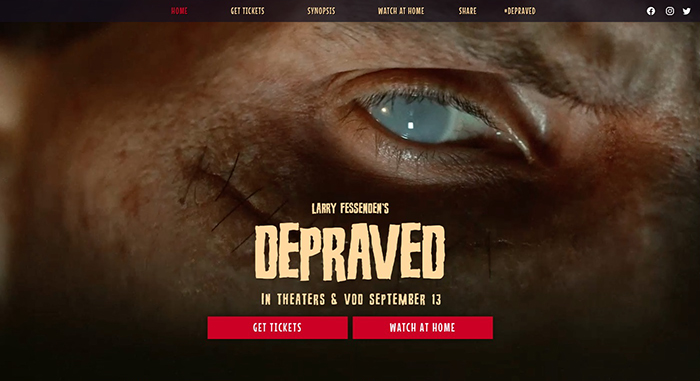

Depraved

Larry Fessenden (2019 114 minutes, RED)

DAVID CALL, JOSHUA LEONARD, ALEX BREAUX, ANA KAYNE, MARIA DIZZIA, CHLOË LEVINE, OWEN CAMPBELL and ADDISON TIMLIN

Henry, a field surgeon suffering from PTSD after combat in the Middle East, creates a man out of body parts in a makeshift lab in Gowanus, Brooklyn. The creature he creates must navigate a strange new world and the rivalry between Henry and his conniving collaborator Polidori.

Nominated — BEST INDEPENDENT FEATURE

Nominated —BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR: Alex Breaux

Nominated —BEST MAKEUP EFFECTS: Gerner and Spears

ONE OF THE 10 BEST HORROR FILMS OF THE YEAR

an inspired Gowanus-grungy DIY Frankenstein,

with director Larry Fessenden pushing through

to the subtext of parentally irresponsible men.

Grabs you with its ideas (and imaginative production moxie).

Somebody buy this.

Depraved might be Larry Fessenden’s best movie yet.

Chicago Now

Joel Wicklund,

Depraved – Though he’s been very busy as an actor, producer and audio drama creator, it’s been 13 years since we’ve gotten a true Larry Fessenden film and it’s good to have him back. Depraved is his second DIY take on Frankenstein, and where the first (1991’s No Telling) dealt with scientific mistreatment of animals, this one centers on the exploitation of humans via war, commerce and science corrupted to serve both of those masters. It has its shaky moments, but Fessenden’s trademark style of tragic horror shines through. It’s also his angriest film to date – a natural response from a filmmaker so concerned with societal ethics who has watched them devolve so quickly.

BifBoomPop

Tim Burr,

Larry Fessenden, another director I absolutely love, bestowed upon the world his modern/urban take on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with Depraved. The film is a towering work of art and hands down my favourite version of this story ever produced.

Indiewire

Eric Kohn,

While ’90s American cinema tends to play up the legacies of auteur superpowers like Tarantino and PTA, Larry Fessenden deserves just as much appreciation. Ever since his 1995 breakout “Habit,” Fessenden has combined a scrappy New York filmmaking aesthetic with genuine frights, and “Depraved” is a welcome return to those roots. A tense, dramatic retelling of “Frankenstein” with modern-day concerns, the movie stars David Call as a surgeon and Iraq war vet roped into performing experiments on a corpse to bring it back to life. When he’s successful, the monster (played by a lanky, corpse-like Alex Breaux) develops a natural curiosity about the world around him, even as he grows cynical about the people teaching him what to do. At once an indictment of technology and the quest to control the natural order, “Depraved” makes the case that Fessenden should really make movies more often, because these troubled times benefit from his spooky voice.

brokeassstuart.com

Jonas Barnes,

This is a movie that screams “indie” through and through. It is a retelling of the “Frankenstein” story that ends up making big pharma the real villain. Filmed entirely in Brooklyn on a shoestring budget, the movie makes incredible use of the location to create atmosphere. Oh, and it’s also a bat shit insane take on the story as well, so it breathes new life into an old classic. Kudos to director and creator Larry Fessenden for pulling off an incredible feat here.

Horror News Network

Larry Dwyer,

Indie horror king Larry Fessenden wrote and directed this modern take on the Frankenstein tale about a PTSD-suffering army medic named Henry who spends his days in his Brooklyn laboratory creating a “man” named Adam out of borrowed body parts (Adam…see what he did there?). This may be Fessenden’s best film to date and also includes great makeup FX by Brian Spears and Peter Gerner who are up for a Fangoria Chainsaw Award for their work. Bravo.

Geeks of Doom

Dr Zais,

Depraved – The best modern Frankenstein adaptation by the master of independent New York horror, Larry Fessenden.

Bloody Disgusting

Megan Navarro, 12/18/19

A PTSD-suffering field surgeon harvests body parts and uses them to create an entirely new man in his Brooklyn apartment. If that sounds like a modern-day retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, that’s because it is. Only this time, it’s through the lens of indie horror master Larry Fessenden, in his first spin back in the director’s seat in years. The result is a refreshing twist to a familiar story, with surprising new depth and poignancy. Moreover, it continues Fessenden’s penchant for maximizing a minuscule budget to create something far more luxurious in style.

The Underlook

Joseph Earp, August 9, 2019

Depraved, like most of Larry Fessenden’s films, starts out as a story that you definitely know: a tormented man named Henry (David Call) assembles a pile of dead bodies and — with a jolt of electricity — brings the mess of flesh to life.

So yes, this is Fessenden’s Frankenstein picture, and like James Whale before him, the New York-based auteur has a lot on his mind about the nature of mortality, art, and the existential terror that comes when you’ve replaced gods with scientists.

But unlike Whale, Fessenden doesn’t have to worry about rushing to his big final setpiece. Fessenden gets to the burning mill eventually, of course — or at least, his version of it — and one of the great pleasures of the film is guessing when it will click into the grooves of Mary Shelley’s story. Yet, for the most part, the film is remarkably bloodless. It’s almost painterly, as Adam (Alex Breaux), the reanimated monster at the heart of the film, visits art galleries, discovers drugs, and is slowly introduced to the pleasures and pains of life. Which of course, is the other Fessenden trademark: a constant sense of surprise.

Depraved has enough to say about the nature of art — and the people who fund it — that it can’t help feeling autobiographical, at least in an oblique sense. But this is no navel-gazing work of self-obsession. Instead, it’s a remarkably open-minded film, one fascinated with people, and ultimately convinced, despite everything else, that they can be good.

The resulting film isn’t just one of Fessenden’s most astounding projects. It’s one of the most unexpectedly extraordinary American movies of the last ten years. That sounds faintly ridiculous to say of a film that opens with a brutal murder and closes with a ten minute climax of pure, fiery destruction. But hasn’t that always been the magic trick of Larry Fessenden? Stripping the recognisable of its parts, until suddenly everything is new, and fresh, and wonderful.

It’s a masterpiece, basically.

L.A. Weekly

Nathaniel Bell, September 12, 2019

Depraved is an indie horror that pumps fresh blood into the familiar Frankenstein formula. You’d expect nothing less from Larry Fessenden, one of the most resourceful contemporary practitioners of the macabre. David Call plays Henry, a doctor suffering from PTSD whose death-haunted stint as an army medic drives him to experiment with bringing forth life from human body parts. He succeeds in creating Adam (Alex Breaux), a triumph that proves temporary when the resurrected “son” fails to adapt to the sinful world around him. Even though you know where it’s going, Fessenden makes getting there fun, scary, and tragic.

Los Angeles Times

Kimber Meyers,

Review: Sasheer Zamata eases into ‘The Weekend,’ Larry Fessenden’s ‘Depraved’ and more

Two centuries after its publication, “Frankenstein” gets a thoroughly modern, utterly disturbing update in “Depraved.” Mary Shelley herself would likely approve of writer-director Larry Fessenden’s fresh take on her classic story, which arrives with all the horrors and themes of the original intact, plus a few new ones for the 21st century.

Adam (Alex Breaux) awakens in a Brooklyn warehouse bearing Frankenstein’s monster’s trademark stitches and remembering nothing of his life before. Henry (David Call) used his skills as an Army surgeon — plus some experimental drugs provided by his friend Polidori (Joshua Leonard) — to bring Adam back to life, but he must teach the lumbering, scarred man how to be a human again. Adam (re)learns everything from speaking to playing pingpong, but he also starts to regain his memories, including the trauma that caused him to end up in Henry’s care.

“Depraved” is smart in its commentary on everything from the evils of the pharmaceuticals industry to the terrors of PTSD, but there’s real heart and empathy here too. Skeptics might question whether Adam has a soul or not, but Fessenden’s film clearly possesses one.

Roger Ebert.com

Simon Abrams,

American indie horror king Larry Fessenden (“The Last Winter,” “Wendigo”) is just as much a pulp fiction aficionado as he is a neo-gothic romantic: his doomed heroes and sorrowful monsters are all messy, small people whose apparent sense of compassion is often dwarfed by their titanic egos and their general cosmic insignificance. Fessenden’s low-budget film horror movies are not the most cuddly (or polished), but his body of work as a writer and director (and producer and editor) is consistent in its investment in human-scaled people. Fessenden’s prickly sense of humanism makes a considerable difference in “Depraved,” his engrossing take on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and maybe his best movie to date.

Set mostly in a decrepit factory by Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, “Depraved” follows three troubled men and a constellation of tragic supporting characters, some of whom are women. There’s Adam (Alex Breaux), a cadaverous amnesiac with prominent scars on his gaunt face and semi-clothed body; and Henry (David Call), an egotistical, PTSD-afflicted ex-army medic and current research scientist; and Polidori (Joshua Leonard), Henry’s boastful, cynical patron, and a wannabe pharmaceutical mogul. There’s also Liz (Ana Kayne), Henry’s concerned girlfriend; and Georgina (Maria Dizzia), Polidori’s aloof wife; and Lucy (Chloe Levine), the kind girl that Adam can’t stop thinking about, mostly because Adam’s not really Adam.

In a former life, Adam used to be beanie-clad hipster Alex (Owen Campbell), before Henry gave him an absurd new name, a battery of radical antibiotics, and an unreliable sort of companionship. Alex was callow, but not unsympathetic: in an introductory scene, he pushes Lucy away when she semi-casually mentions that he would make a good father. Alex is a mess—anxious, untrusting, young—but also real enough. Adam is somewhat similar, a child looking for guidance and love. His innocence draws people to him like a magnet, partly because everybody in “Depraved” is living on borrowed time, but doesn’t want to admit it, as Fessenden often reminds us through blunt, but effectively pulpy dialogue, and lo-fi psychedelic imagery (the movie’s trippy visual/optical effects are credited to cinematographer James Siewert).

One of the most charming aspects of “Depraved” is the way that Fessenden is able to synthesize his pet themes into a lo-fi psychedelic multi-character study. But you don’t have to be familiar with his work to appreciate the idiosyncrasies that make “Depraved” such a stirring horror movie, though it certainly doesn’t hurt (check out “Skin and Bones,” his 2008 entry in the short-lived TV anthology series “Fear Itself”). Everything you need to “get” this movie is in the movie, so while Fessenden’s generally soft-spoken characters sometimes declaim their intentions, that’s only because they are young and careless (ex: “Most of America is on drugs” and “Henry, you brought the war home with you …”). Fessenden also tends to rely on horror archetypes—the nouveau riche villain, his Byronic surrogate sons, and their worried muses—but only because he likes all of them too much to completely deconstruct or dismiss them. Fessenden’s also probably more of a hippy and/or fatalist than many viewers will be comfortable with, especially given his bleak view of humanity as a daisy chain of small-minded, unhappy creatures who’d rather preserve their lives than embrace their mortality. His characters are, in this way, doomed to inhabit roles that were prescribed to them as soon as Fessenden decided what type of horror story “Depraved” is.

But what’s most remarkable about “Depraved” is the way that Fessenden makes you care about his characters, even when you know that they’re either too kind or too greedy to live. Polidori is the hardest character to warm up to: he wants to be a father figure to Adam because Henry is too proud to accept his benefactor’s cruel, over-simplified view of humanity. Polidori also tends to speechify about humanity’s fleeting genius, like when he gives Adam a guided tour of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and airily dismisses the whole institution as a “mausoleum to the aspirations of man.”

It’s also hard to accept the peripheral roles that women like Liz play in Adam’s story, though Fessenden is characteristically sensitive enough to give his actresses enough space to inhabit their respective roles. I’m especially taken with the scene where Adam tries to bond with Shelley (Addison Timlin), a warm, but wary local barfly who thinks Adam looks like Iggy Pop. This scene’s inevitable conclusion annoyed and saddened me the first time I saw “Depraved,” but made more sense the second time around; this scene captures the pulse of the movie’s bleeding heart. “Depraved” may not take you anywhere that you haven’t been before, but it might leave you with a renewed appreciation for Shelley’s mythic story.

The Wall Street Journal

John Anderson,

Film Review: ‘Depraved’: Playing God and Serving Mammon

Larry Fessenden is a Promethean figure in the world of New York independent cinema, specifically horror, with a generous list of credits as a producer but an almost penurious number as director. Among the latter, the cult-fave “Habit” (1997) was the first thriller to draw metaphorical links between AIDS, sex and vampires; “Wendigo” (2001) was a tour de force of calibrated anxiety; and “The Last Winter” (2006) married arctic madness to environmental exploitation. If Mr. Fessenden had a gospel to preach it would be about the virtues of low-budget, intellectually rigorous, topical, mayhem-rich movies. Of which “Depraved” is a perfect example. Serving as writer, producer, director and editor, Mr. Fessenden has reimagined “Frankenstein” less as a parable of hubris than an indictment of modern medicine, Big Pharma and war. But hubris, too: Having served as a doctor in an unspecified Mideast battle zone, Henry (David Call) has returned with a case of PTSD that manifests itself in a crazed compulsion to preserve life at any cost — and to re-create it if necessary. When a young man named Alex (Owen Campbell) is viciously knifed on a Brooklyn street — why and by whom are matters we’re never quite sure about — his brain becomes the last piece in Henry’s puzzle: how to make a whole man out of parts, in this case the creature called Adam (Alex Breaux), who awakens in Henry’s makeshift Brooklyn laboratory looking like he’s just been autopsied and knowing nothing about who or where he is. Henry is playing God, a la the original Victor Frankenstein, but in this case the Almighty also has a profit motive: Financed by a college friend, Polidori (the degree of repugnance Joshua Leonard generates in the role is a credit to his performance), Henry is defying nature, but also testing a not-yet-FDA-approved drug that prevents organ rejection. Adam may look like a car wreck — Mr. Fessenden has to throw a few bones, shall we say, to his slasher/splatter base — but the newly made man is also a walking, halting, almost-talking test case for the formula Polidori plans to sell for untold millions. Mr. Fessenden is a first-rate director of actors — Mr. Breaux, for one, gives an unnervingly good performance — and a first-rate editor: The rhythms established, from the moment Alex leaves the Gowanus apartment of his girlfriend, Lucy (Chloe Levine), to Adam’s comic/tragic encounter in a bar with an Iggy Pop fan (Addison Timlin), to the climactic scenes at Polidori’s Prussian-castle-like country house, are meant to rub nerves raw. There may be a few too-obvious flourishes. The snatches of German Expressionist set design are an obvious homage to the James Whale-directed Frankenstein films of the ’30s (and, even more so, “Son of Frankenstein”); we needn’t be told outright that “Henry” was the name given the Frankenstein of those movies. And when Polidori drags Adam off on a jaunt that includes both a strip club and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, his privileged, nihilistic spiel about the meaning of life is almost too predictably hateful. The art, however, is articulate: Adam gazes at a Jackson Pollock — “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” it seems to be — and sees in the painting the same animated, subatomic images that have been recurring in his head throughout the film. And when we see Jean-Leon Gerome’s “Pygmalion and Galatea” — the statue having come to life, and embracing the artist — it puts a punctuation mark on the mythos and epic that Mary Shelley conjured up, and on which Mr. Fessenden puts such a delightfully gritty, sometimes gruesome spin.

New York Times

Jeanette Catsoulis,

‘Depraved’ Review: Busy Body (Parts)

Larry Fessenden updates Mary Shelley’s classic tale, “Frankenstein,” producing possibly his most coherent and visually polished work yet.

Henry (David Call), the doctor in Larry Fessenden’s “Depraved,” isn’t actually called Frankenstein, but he’s the contemporary equivalent. A onetime Army surgeon, Henry suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and a maniacal need to make positive use of his harrowing experiences. What he learned about death, he believes, he can use to create life.

The result of this obsession is a bundle of stitched-together body parts known as Adam (Alex Breaux), whose brain we meet while it’s still inside the skull of its about-to-be-murdered previous owner. That organ’s memories — often surrounded by bright bubbles of light, as if trapped in a lava lamp — help bond Adam to his creator, whose battlefield flashbacks are equally destabilizing.

In time, their relationship grows quietly touching; yet if Henry’s motives seem pure, those of his cynical business partner (Joshua Leonard) are anything but.

Shot in just 24 days in Brooklyn, N.Y., “Depraved” updates Mary Shelley’s classic tale with a coating of wartime trauma and medical-breakthrough profiteering. Making the most of his limited budget, not unusual for the prolific Fessenden, he has produced possibly his most coherent and visually polished work to date. The makeup effects and lead performances are excellent, and Fessenden’s signature cheek (two strip-club employees are called Stormy and Melania) never tips into silliness.

Though overlong and leaning predictably on old-school horror setups — like the beautiful barfly (this one is played by Addison Timlin) who trustingly toddles home with the monosyllabic weirdo — “Depraved” builds empathy for its exploited creature. Beginning with lovemaking and ending in loneliness, the movie has an unexpected poignancy: At the end of the day, it seems, all a monster really wants is a girl of his own.

Rue Morgue Magazine

Michael Gingold,

MOVIE REVIEW: LARRY FESSENDEN’S “DEPRAVED” IS ALIVE WITH IDEAS, DRAMA AND TERROR

The release of DEPRAVED this week reminds us how long it’s been since Larry Fessenden has brought one of his own stories to the screen, how much he’s been missed and how vital his personal point of view on the genre continues to be.

DEPRAVED is his own take on the Frankenstein story; he’s explored variations on the theme before (his early feature NO TELLING was a bad-science shocker subtitled OR, THE FRANKENSTEIN COMPLEX), and this one hews closer to the basics and themes of Mary Shelley’s classic while forging its own modern path through the material. In so doing, Fessenden employs what at first seem like traditional tropes but prove to have deeper meanings. He opens with a fairly explicit sex scene between a couple of good-looking young people (SUPER DARK TIMES’ Owen Campbell and THE RANGER’s Chloë Levine), which is far from gratuitous raunch: It’s a depiction of the purest act of creating life, made clear by their subsequent discussion about whether the guy is ready for fatherhood. These are signifiers of the themes the writer/director will go on to explore in DEPRAVED, chiefly those of responsibility, both parental and scientific.

Fessenden’s protagonist, like that of James Whale’s classic 1931 FRANKENSTEIN, is named Henry (David Call), though if he shares the famous surname, it’s not revealed in the film. A former military field surgeon scarred on the inside by his experiences in the Middle East, he takes the time-honored path of attempting to cheat death by creating life—with the help of his Big Pharma sponsor, named Polidori (after one of the other writers at the fateful Geneva get-together that spawned Shelley’s novel) and played by Joshua Leonard. The details and forces behind the “monster’s” vivification are backstory to be discovered and revealed, however, since this is one of the rare Frankenstein films to tell its story from the point of view of its man made of corpse parts, a gambit that proves to be successful and crucial.

Named Adam (Alex Breaux) by Henry, he wakes up a mess of scars and confusion in the doctor’s Brooklyn-loft laboratory, unable to speak or comprehend the environment around him. He’s a vessel into which Henry only wants to pour the best intentions, and Call and Breaux evoke a profound relationship that is at once parent and son, teacher and student, experimenter and experiment. Breaux, emoting under Brian Spears and Peter Gerner’s excellent prosthetics—scars that come to evoke pity rather than repulsion—projects deep feelings of humanity struggling to come to the surface, while Call’s Henry feels genuinely motivated to mold him into a proper human, and to protect him from the vagaries and treacheries of the society outside his lab.

Polidori, on the other hand, has no such concerns. Anxious to reveal the fruits of his sponsorship to his backers, he becomes a sort of cool dad to Henry’s concerned, sheltering father, exposing Adam to the world, taking him to both an art museum and a strip club. But it is when Adam ventures to a local bar on his own, and shares an affecting scene with one of the patrons (Addison Timlin), that his inability to properly function in society—and the unfortunate ramifications—become clear. He is a scientific product not yet ready to graduate from alpha testing, but unleashed upon the world anyway, making him very much a “monster” of his time, and part of Fessenden’s allegorical study of an Information Age world in which value is placed on getting and knowing things faster, not necessarily better.

DEPRAVED is also the emotional saga of one (artificial) man’s attempts to comprehend and come to terms with his past, as flashes of Adam’s previous existence as someone else begin sparking in his stolen brain. And through it all, Fessenden never forgets he’s also making a horror movie, a side that becomes more pronounced in the final third, when he and cinematographers Chris Skotchdopole and James Siewert ease from downtown gritty to full-bore rural Gothic. The production values in general, low-fi though they might be (Fessenden made DEPRAVED on a tiny budget after years of trying to mount it as a higher-profile production), feel very right to the material, and Fessenden’s thesis that science can be mishandled on a personal as well as a corporate level, with the same unpleasant cost to individuals. Moving and frightening and exciting in its intelligence, DEPRAVED is another standout in Fessenden’s filmography, joining a (ahem) body of work that draws from disparate sources but fits together far more cohesively than the patchwork Adam.

The Hollywood Reporter

John DeFore,

Genre stalwart Larry Fessenden offers a modern take on the Frankenstein story.

A modern take on Mary Shelley’s classic novel that focuses on psychology and capitalism over science and scares, Larry Fessenden’s Depraved transports Frankenstein and his creature to Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood, circa last week. (No jokes about other monsters that might spring from that filthy canal, please.) David Call and Alex Breaux play papa and stitched-together creation, respectively, in a film that is serious but not pretentious, working best when it stays in the laboratory. It will be welcomed by the director’s fans, and may expand that number somewhat in its limited theatrical release.

Unlike most versions of the tale, this one begins with a poor soul who’s about to become raw material: Owen Campbell plays Alex, a sweet-seeming youth just out of college, having an argument with his equally sweet-seeming girlfriend Lucy (Chloe Levine). The two argue over expectations about their relationship’s future, he leaves to clear his head, and he’s brutally murdered by a mugger.

Alex awakens in another man’s body (or, more likely, a patchwork of several), his freshly transplanted brain unable to make sense of things. In appealing FX work, some superimposed graphics (tracers, firing synapses, et cetera) suggest what’s going on in the rewired gray matter; but as the being about to be named Adam, Breaux does a very fine job of conveying that confused state by himself.

Adam doesn’t awaken to the sound of a mad scientist’s “It’s alive!!,” though dramatic lightning storms will play a part later in the tale. He’s by himself, rising from an operating table in an industrial loft sparsely furnished with thrift-store decor. Henry (Call) is astonished when he returns to the lab and finds him; he speaks gently and, over the next few days, tests Adam’s motor skills and intelligence. Initially, Adam fails to solve the simplest puzzles, but soon he’s playing ping pong, using an iPad and reading serious literature when Henry’s away. Then Liz arrives.

Liz (Ana Kayne) is Henry’s ex-girlfriend, part of a quartet of college friends that also includes Joshua Leonard’s Polidori. The latter became rich when he married Georgina (Maria Dizzia), and began secretly funding the revivication research that Henry started during his time as an Army trauma surgeon. Henry’s work springs from PTSD and guilt; Polidori is hoping his successes will prove the commercial viability of a drug he wants to sell. Liz, a therapist, just wants to keep the men from treating this new creation like a toy to fight over.

With the exception of a sequence in which Polidori whisks Adam off on a day trip that starts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and ends at a strip club — louchely, he makes himself tour guide through the high and low extremes of human existence — the film’s first half stays loft-bound, seeing things from Adam’s perspective. He is soft-spoken and gentle, feeling his way through the world but seemingly less likely than a real child to believe everything he is told. Flickers of loneliness emerge early on, as do fragmented memories of the life history that died with Alex. Even without Polidori’s heedless rush to get this “product” to market, it’ wil soon get hard to keep Adam locked away and docile.

Yes, exploration will lead to bloodshed and some mayhem. But Fessenden reimagines things, keeping the story fresh even if not every aspect of it rings true. (Adam’s first outside encounter with a woman, for instance, fits the screenwriter’s needs too neatly, and some of the fallout strains credibility.) Still, the film captures the cost of Henry’s well-intentioned sin, following this pained new creature out into the world and, very briefly, giving his suffering an almost Malick-like voice. The pic’s title and its Karloff-evoking poster are as horrible as things get in this portrait of a monster as victim of human hubris.

Eye for Film

Jenny Kermode,

Mary Shelley’s genre-birthing novel Frankenstein, Or The Modern Prometheus was first adapted for the big screen in 1910 and has been reimagined there more than a dozen times since, whilst its central characters have appeared in numerous spin-off stories. Depraved is a sidelong take that shifts the action to the present day and the primary perspective to the monster. Unexpectedly sweet, it’s one of the finest to date.

To horror fans, the name Larry Fessenden suggests low budgets, low life characters and a punkish, even parodic visual style. Depraved adopts some techniques popular within this oeuvre but uses them to enhance the intimate personal drama at its core rather than to create sensation. From the opening shot, in which we drift through a modest but lovingly furnished apartment to witness a young couple making love and arguing afterwards as only those who are deeply in love do, it’s clear that Fessenden knows exactly what he’s doing. There has often been a sense of tragedy in his work and here it’s almost omnipresent – which doesn’t mean that there are not some very funny moments along the way.

The young couple whom we first meet are Alex (Owen Campbell) and Lucy (Chloë Levine, with whom Fessenden worked on last year’s [flm id=33657]The Ranger[/film]). They’re so lovely together that in context, one immediately fears for them – this kind of warmth cannot last. Sure enough, violence comes from out of nowhere and before we know it, Alex is waking up in a strange place, on what seems to be an operating table – except he’s not Alex any more. His body is different (he’s now played by Alex Breaux) and covered in surgical staples and scars. The man who enters the room and tries frantically to calm him down keeps calling him Adam.

This man is Henry (David Call), a gifted surgeon and one half of an ambitious medical start-up company. As we only see him through Adam’s eyes, it takes a while for the details to begin clear. To begin with, Adam can’t understand speech or manage even basic tasks like attending to his own toilet needs. He’s entirely dependent on Henry, who imagines himself as a father, presenting a succession of educational toys. Adam is a quick learner and it doesn’t take him long to figure out that he’s different from other people, to become curious as to why that is. In a sense this is a coming of age story, and as emotionally involving as such tales usually are – but inevitably, Adam’s dawning understanding of his predicament leads to trouble.

At the centre of the film, Breaux is superb, not only capturing the pathos vital to the monster but carrying him through the long, slow process of cognitive development and emotional realisation without ever striking a false note. One of Fessenden’s most bitter an poignant observations is that in today’s America a stitched-together, barely articulate monster can wander through the streets of a major city with nobody batting an eyelid because he’s assuming to be just another relic of the war. Indeed, wartime experiences are a big motivating factor for Henry (as they once were for a certain Herbert West), and they attract a bit of sympathy to a character who is otherwise deliberately presented as shallow, at odds with the monster’s deep emotion. As petty squabbles break out between the business partners, the women in their lives and potential clients, Adam observes from a distance, increasingly aware of their shortcomings, the extent to which they fall short of the human ideal.

The film builds slowly, deliberately, inviting us to invest in the simple joys of being alive before lurching into inevitable, delirious violence. It’s confidently paced and waits for exactly the right moments to shift gears. Fessenden’s visual style makes it utterly immersive. Though it’s still likely to be too quirky for some viewers’ tastes, it’s a triumphant piece of outsider cinema which will sear itself onto the consciousness like Promethean fire.

Slant

Steven Scaife,

Review: Depraved Views Modern Society Through the Lens of Frankenstein

What does a Frankenstein figure look like in 2019? According to Larry Fessenden’s Depraved, he’s a guy with war-addled, once-noble intentions set adrift by male ego and shady benefactors. He’s a white man grasping for control in a world coming apart, a cog in a machine who hasn’t broken free so much as changed the machine’s function—from that of war to that of the pharmaceutical industry. The film, Fessenden’s first feature as both writer and director since 2006’s The Last Winter, paints multiple psychological portraits that are sad, angry, and strangely beautiful. It shows us the mind of not just PTSD-afflicted field surgeon Henry (David Call), but also that of his prototypical sewn-together “monster,” Adam (Alex Breaux), and his assistant and Big Pharma bankroller, Polidori (Joshua Leonard).

For much of Depraved, Fessenden’s focal point is essentially the monster’s brain, which starts in the body of a man named Alex (Owen Campbell) before being unceremoniously transplanted to its final container in Adam, whose ghastly scars and stitches betray his unnatural heritage. Aside from vestigial flashes of his former life, Adam is a vessel to be filled with the perspectives of those around him. Fessenden devotes long stretches of the film to that learning process, an enthralling canvas for his usual bag of editing tricks.

As Adam’s brain develops and reconfigures, the screen is covered in green blots, time-lapse constructions, hyperactive movements, montages, and other music video-esque trappings that somehow are never incongruously showy so much as a mesmerizing fit for the material. In Wendigo, such flourishes followed the film’s spiral of supernatural unease, and in Depraved they give Adam’s learning process an odd, hypnotic beauty. Fessenden imposes brain scans and firing synapses over the screen as characters’ voices echo for an effect that compares these parts of the human body to the fingers of tree branches or the forks in a peaceful forest creek. Adam’s thoughts and feelings are natural, even if his existence is not.

His hair grows, his speech patterns diversify, he reads, and we learn what Henry deems important by what he teaches Adam as foundational, or what he doesn’t teach him at all. “Gravity is your friend,” one lesson goes, and then Henry drops a bouncy ball. Adam may not learn how to shake hands until he meets Polidori, but he learns how to play ping pong. In his loneliness, Henry has built himself a buddy, albeit one he may control and whose interests he may dictate. When he teaches Adam about music, he mentions Bach and Beethoven because they’re important, but you sense him skipping to the important stuff, to the music he personally likes. He’s the date who invites you over to tell you about his record collection.

At the museum, Polidori and Adam linger on a self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh, noting the similarity between the painter’s ear and Adam’s, which is discolored and conspicuously sewn on. But Van Gogh cut off his own ear; no one cut it off for him. So who’s the artist in this relationship? Is it Adam or Henry or Polidori, who supplies the body parts and the money and is named for John William Polidori, the writer who both played a small role in the creation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and himself penned “The Vampyre,” one of the first vampire stories? With bad blonde hair and names for strippers including “Melania” and “Stormy,” Fessenden paints him as a Trump-like figure, a talentless bloodsucker.

The comparison is far from graceful. Though Fessenden’s films leave no mistake as to what they’re about, the characters of Depraved feel overly prone to calling out the obvious, ensuring that each name-drop and reference is processed appropriately by the audience. But if, as in the somewhat baggy final 30 minutes, the film’s thematic reach exceeds its grasp, it remains firmly focused on its thesis of Frankenstein as a lens for examining modern society. Throughout Depraved, Fessenden catalogues what personalities and power dynamics have shifted and what hasn’t changed at all. The filmmaker diagnoses the rot of our era through these solipsistic men that pour their prejudices and their insecurities into Adam, an open book eventually read back to its authors with a violence they cultivated themselves.

Time Out New York

Joshua Rothkopf, September 4—17 2019

Larry Fessenden, the indie=horror stalwart, has emerged with his most invigorating nightmare in years; an update of Frankenstein that accommodates post-Iraq War trauma, shady Big Pharma funding and the mysterious things that go down in a Brooklyn loft after midnight. Adventurous souls should make it a priority

Cinemaniac

Dennis Dermody, 3/17/19

Depraved. Larry Fessenden’s macabre, inspired take on the Frankenstein story is heartbreaking as it is horrifying. Set in a warehouse/loft in Brooklyn, Henry (David Call) is a former army surgeon suffering PTSD who has stitched together body parts and brought to life Adam (Alex Breaux). He reluctantly becomes a father-figure to this re-animated creature, training Adam how to talk, think, dress himself, play puzzles and ping pong and learn that “gravity” is his friend. Fessenden gets to the core of Mary Shelley’s story, this go-round the science used is more drug-related that electrical. But it also gets the folly of the God-like doctor learning to regret and fear his own creation. Alex Breaux’s performance is stunning in its physicality and pathos. Fessenden truly is a hero of mine- he has consistently made some of the most lyrical, bizarre, thought-provoking genre films. This Frank ‘N The Hood is one of his very best.

Indiewire

David Ehrlich, 3/19/19

‘Depraved’ Review: Larry Fessenden’s No-Budget Delight Brings Frankenstein into the 21st Century

Indie horror maestro Larry Fessenden refashions Mary Shelley’s immortal novel into a modern story of trauma and self-interest.

Hell-bent upon finding evidence of ancient monsters in the modern world (often by exploring how they continue to be reflected in the raw stuff of human nature), Larry Fessenden launched his filmmaking career with a Frankenstein story, and he’s been working his way back to the subject ever since. Traces of Mary Shelley’s mad science can be found in many of the low-budget horror movies that his Glass Eye Pix has produced since 1985, and they’re even more apparent in the ones that he’s directed: From the ecological hubris of “The Last Winter” to the monster-is-us mythicism of “Wendigo” and the selfishness that percolates beneath all of his narratives and bubbled to the surface in “Beneath,” each of his features has dissected a severed limb from Shelley’s foundational story.

With “Depraved” — which is perhaps both his least expensive and most ambitious movie — Fessenden sews his entire body of work together. More than a masterclass in DIY cinema, the result of this deranged experiment is a fun and febrile tale that takes the moral temperature of our time with an almost invasive degree of accuracy. If Fessenden’s reach inevitably exceeds his grasp, well, whose doesn’t these days?

Shot on the 200th anniversary of Shelley’s novel (after more than 15 years of kicking around Fessenden’s head), “Depraved” wasn’t conceived as a no-budget riff on a story that’s traditionally been adapted by large studios, but none of the bigger fish were taking the bait. But Fessenden, a Dr. Frankenstein in his own right, wouldn’t let a lack of cash get in the way of his creation. And so, with the help of some talented collaborators and a very flexible Gowanus warehouse, he forged ahead on a film that resurrects Shelley’s 19th century masterpiece with a decidedly 21st century mentality. This is a Frankenstein for the “move fast and break things” era, for a time when people really can fuck with God from their parents’ basement, and every tech giant from Facebook to Theranos is flying by the seat of its pants. The world changes faster than we do, but we can always see our true selves reflected in our visions for the future.

“Depraved” begins on its most benign note of recklessness, as a couple of Brooklyn twentysomethings (Owen Campbell and Chloë Levine) have a stilted post-coital argument about commitment; she wants him to stay over, but he’s already gotten what he wanted. Needless to say, you won’t be particularly heartbroken when the guy gets stabbed on his walk home. From there, he’s dragged to a scuzzy laboratory nearby, where his wet brain is transplanted into the stapled, alabaster body that Henry (David Call) has been stitching together in secret.

With the final piece in place, Henry — a grieving but gifted field medic who’s suffering from PTSD after serving in the Middle East — is ready to flick on the lights. And so Adam (Alex Breaux) is born. A mute and mangled collage of different corpses who’s brought to life by a mysterious drug, the careful precision of Breaux’s cyborg-like performance, and also the brilliant makeup work of Peter Gerner and Brian Spears, Adam is a far cry from the lumbering green oaf that James Whale made into a Universal icon (think Alex Pettyfer’s character from “Beastly,” only much less humiliating). He’s like a reformatted computer that’s been assembled from old scraps. And Henry, who’s sweeter and more optimistic than Dr. Frankenstein ever was, can’t wait to program him. His old-money financier (“Unsane” actor Joshua Leonard as the single-minded Polidori), has other ideas. The rest is history: Men become monsters, monsters become men, everyone flies too close to the sun, and gravity takes its toll.

Despite the twisted implications of its title, “Depraved” is a rather sensitive, emotionally-driven story that’s at its best when its characters engage one another with the best of intentions. The film is seen through a woozy subjective haze (James Siewert contributes a clever lo-fi effect to get into Adam’s headspace, as colored lights fizz and pop across the entire screen to suggest his synaptic connections), and the first half in particular is padded with a gauze-like softness.

Surprised by Adam but only repulsed by himself, Henry becomes the heart and soul of the movie, and Call’s delicate performance walks a fine line between altruism and self-interest. To what extent is Henry conducting these experiments for the benefit of all mankind? To what extent is he just perverting the laws of nature in order to quell his personal grief over not being able to save his fellow troops? It’s hard to say — especially for Henry. Whether teaching Adam how to play ping-pong, or introducing Henry’s creation to his semi-estranged girlfriend (Ana Kayne), Call is always wrestling with the destructiveness of his character’s salvation, and always using one eye to watch how Henry’s worst impulses are borne out by Adam’s behavior. “Depraved” offers a skewed glimpse at what “The Social Network” might have been like if Mark Zuckerberg had a conscience.

That comparison extends itself to the film’s structure, which is linear but unstable. “Depraved” only moves in one direction, but it possesses different people as it goes along, and looks at Adam from their perspective. Fessenden’s approach reflects the shape of Shelley’s novel (at least to a certain extent), and stresses how everyone brings their own kind of moral equivocation to these grotesqueries. Polidori hijacks the story in order to show Adam some culture, and then Henry’s girlfriend slips in to show Adam some affection; the impressionable golem soaks up what he sees like a sponge, and becomes a fun-house mirror for the self-interests of those he meets. It isn’t long before strangers become potential victims (Addison Timlin, who co-starred with Fessenden in the dementedly brilliant “Like Me,” gives the movie a well-timed shot in the arm as a curious bar-dweller who’s too kind for her own good).

For the most part, however, “Depraved” suffers for pulling focus away from the fragile bond between Henry and Adam. As a caricature of start-up culture, Polidori is a poor complement to the wrenching journey that the rest of the characters are on; Fessenden wanted to make a version of “Frankenstein” where we feel empathy for both the monster and his creator, but he may have underestimated how successful he was in doing so. Henry brings the war home with him so vividly that his brewing conflict with Polidori is hard to believe in comparison.

It’s as if Fessenden, whose work has always satirized human selfishness, is a bit uncomfortable with the idea of taking it seriously. The tortured nuance of the film’s core gives way to a broad throwdown between right and wrong, and the DIY charm that “Depraved” relies on to stress how we’re all stuck in a horror movie is replaced by an overextended attempt to make this story feel larger than life. It’s possible that Fessenden — who finds a satisfying way to bring the story home — has succumbed to the same American exceptionalism that fuels so many of his characters. More likely, he was seduced by the scale of the original “Frankenstein” story. Either way, “Depraved” has the brains to survive all sorts of mottled damage to its body, and resolves as a welcome reminder that independent cinema would be a better place if everyone shared Fessenden’s ambitions for it.

The Hollywood News

Kat Hughes, 3/21/2019

‘Depraved’ Review: Dir. Larry Fessenden (2019)

Depraved Review: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein gets a modern day cinematic retelling in Larry Fessenden’s latest movie Depraved.

Filmed during the bicentenary of Mary Shelley’s classic novel, Depraved is a modern day interpretation of the Frankenstein story. Alex (Owen Campbell) is about to move in with his girlfriend Lucy (Chloe Levine). The pair are very much in love, but after an argument over starting a family, Alex takes to the streets to cool-off. Here he is attacked by an unknown assailant. When he awakens he is not quite himself, literally waking-up in another body, one that appears patched together with stitches. He is now Adam (Alex Breaux), an experiment in resurrection by ex-forces medic Henry (David Call), a brilliant mind tarnished by PTSD, and Henry’s old college buddy Polidori (Joshua Leonard) whom bankrolls the study. Slowly ‘Adam’ starts to learn about the world around him whilst trying to recover the Alex part of himself. All is going well until Adam uncovers the truth of his ‘birth’…

Whilst the Frankenstein story has been told hundreds of times across the world of cinema, Depraved somehow manages to feel completely fresh. Directed by genre icon Larry Fessenden, Depraved gives plenty of nods to Shelley’s work, while at the same time standing on its own. Here, our Doctor Frankenstein character isn’t a simply a mad scientist, but rather a war-damaged ex-soldier suffering with PTSD. The sights that he witnessed on tour have shaped him and his need to stop death. Filling the more traditional Doctor role we have Polidori, a man in it purely for the money and notoriety of achieving the achievable. Both are narcissists, and both have very different ways of handling Adam; Henry chooses to give him games and culture, Polidori shows him alcohol and strippers, but both ultimately let him down. It is their actions that shape Adam, shining a light on the importance of a parental role. The creature therefore is not what has become the common trope of a simpleton brute. Adam is much more the innocent wide-eyed child whose world becomes complicated when confronted with the viciousness of adulthood and the brutality of his reality.

With characters that are so deeply intricate and layered, casting is very important. These roles are so familiar that they could all too easily be played with the traditional over-the-top vigour, yet leads David Call and Alex Breaux both reign their performances back. Yes, Henry has something of a God complex, but he’s not completely mad. Call plays him as a truly broken, but still stubborn obsessive, and elicits his own sympathy from the audience. Breaux is rightly the performer of the film though, with his elegant take on the famous movie ‘monster’. His performance takes the viewer on an emotional journey of growing-up. When we first meet his Adam, he is full of innocence and wonder, but as he rapidly ‘grows-up’, we see how the world breaks his spirit. Breaux tackles the role with gusto and gives such an intimate insight into the creature that, not only is his eventual rage completely justified, he also manages to break your heart.

It’s not just Breaux and Call that shine though, Fessenden has captured a cast full of strong actors who all hold their own in their respective roles. The Blair Witch Project‘s Joshua Leonard oozes sleaze and depravity, remarking to Adam, “Depraved. That’s what we are Adam, initially depraved,” and fully living up to that mantra. Ana Kayne offers a third, more emotionally invested parent to Adam, as Henry’s ex Liz. The Ranger‘s Chloë Levine is suitably sweet as Adam/Alex’s girlfriend/heart Lucy, and Addison Timlin’s Shelley, whom Adam meets in a bar, is wonderfully tragic.

In addition to the cast, Fessenden, whom as well as directing, wrote, produced and edited Depraved, has put a great deal of thought into every aspect of the production. The setting – a warehouse turned makeshift apartment – feels equally rundown, isolated and clinical. Will Bates’ score is a haunting blend of electronics and real world noises. The creature design on Adam is simply superb. When you first see Adam in full, it’s a truly shocking sight to behold, and the work by Gerner and Spears Effects is worthy of awards. Hidden amongst their work are subtle nods to many previous Frankenstein creatures, it’s very nice inclusion, and one that highlight’s Fessenden’s clear love for the icon. The visuals are beautifully put together. There are several moments where the cinematography is perfectly layered with bright colours jutting across the screen, mimicking Adam’s neurons and synapses as he takes in the world around him. Similarly, there are shots of cloudy fluids imposed over the top of Adam’s injection sequences. These add an ethereal, almost fairy tale quality, and take some of the sharpness. Even the end credits are a delight to look at, Fessenden forgoing the usual black in favour of anatomical sketches of the human body. Finally, there is a moment during the climax where things get a little black, white and sepia in tone, which when coupled with Breaux’s performance, create the perfect throwback to the old-school Frankenstein films.

Depraved is easily identifiable as a Frankenstein story, but brings in more modern aspects, and a there’s a treasure trove of issues explored – nature versus nurture, man versus science, love versus lust, and life versus death. Somehow Depravedraises all these points without becoming overwhelming, rather it entices the viewer to watch again and again to discover new things. A film of true beauty, both creatively and performed, Depraved is anything but what the title suggests. A truly special moment in the lineage of a beloved movie monster, Fessenden has crafted the best take on Frankenstein since Shelley herself.

Film Threat

Lorry Kikta, 3/21/2019

Depraved

What all these films have in common is that they are quite clearly Frankenstein adaptations. With Larry Fessenden’s newest film, Depraved, it’s not thrown in your face. If anything, I saw parallels more immediately to Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator, which itself is a loose adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s Herbert West: Re-Animator. It can be argued that the serial novelette of Lovecraft’s is a bit of a “re-imagining” of Frankenstein as well, but that’s a story for another time.

Depraved is the most modern interpretation of the ideas brought forth in Frankenstein and Re-Animator thus far. In the beginning, we meet Alex (Owen Campbell) and Lucy (Chloë Levine). A young couple in love and about to marry. It seems as though things are going to go great for them, but you go in knowing this is a horror movie, so of course, that isn’t the case. Alex gets attacked randomly on his walk home from Lucy’s apartment. He doesn’t survive the attack.

“There’s a pill called RapidX that helps speed up Adam’s recovery from…being a human jigsaw puzzle…”

We are then taken to a Gowanus Loft (that I would totally live in, in case anyone wants to give me some info on how to rent it) where Henry (David Call), a doctor who served in the Iraq war has been conducting some rather unorthodox experiments. Shortly after being introduced to this setting, Henry’s patient wakes up. The patient is of course “The Monster” or as he is called in the novel, Adam (Alex Breaux). When he first wakes up, Henry can’t believe it. He’s overjoyed with this ability to bring people back from the dead.

Henry’s partner in this venture, Dr. John Polidori (Joshua Leonard) is the one with the money that made all the experiments possible. He also works for a big pharmaceutical company. There’s a pill called RapidX that helps speed up Adam’s recovery from…being a human jigsaw puzzle. It doesn’t take too long before Adam can talk, play ping-pong, read hundreds of books, become interested in women, and have memories from the brain of its original…owner. Henry is a bit overwhelmed by how quickly this is taking place, but Polidori is incredibly excited. Henry’s girlfriend Liz (Ana Kayne) is none too pleased with how secretive Henry is about this work. Adam is a little bit too fond of Liz.

If you’ve seen any iteration of Frankenstein or Re-Animator, you know these things don’t usually end well for the doctor, the patient, or anyone else involved. However, in Depraved, Henry (who Polidori refers to as “Henry Frankenstein” towards the end of the film) is suffering from severe PTSD, and that is his reason for being obsessed with bringing people back to life. Polidori is the real “villain” if there is one. Towards the end of the film, there are numerous nods to the Universal film with Boris Karloff, which are great little Easter eggs.

“So if you want to see an awesome punk rock New York Frankenstein movie from the director of Wendigo, you should check out Depraved.”

The whole cast is excellent, but I particularly loved Alex Breaux as Adam. You empathize more with him than you do with any of the supposedly more human characters. Adam shows us the purity of innocence and the sadness when that innocence is destroyed. I also thoroughly enjoy Maria Dizzia as the disaffected, annoyed wife of Dr. Polidori, Georgina. She’s usually great in everything, and this performance is no exception.

There are a lot of psychedelic visuals and creepy lighting that fits the mood of the film. Overall I would refer to this as the punk rock Frankenstein movie. There’s one part where Adam is in a bar, and a girl named Shelley (Addison Timlin) tells him he looks like Iggy Pop. He then tells her his name is Iggy and The Stooges are playing in the bar while the whole interchange is happening. The film also shows the creepy grittiness of the particular part of Brooklyn near the Gowanus Canal that can feel pretty scary at night. Depraved is also a grand tour of South Brooklyn. There are also some great scenes at The Met. So if you want to see an awesome punk rock New York Frankenstein movie from the director of Wendigo, you should check out Depraved. If this doesn’t sound immediately interesting to you, I don’t know if we can be friends. I’m sorry.

SCREEN ANARCHY

Jamie Grijalba Gomez, 03/22/2019

Larry Fessenden has always been among the most recognized and loved directors in the underground indie horror scene, with films like Wendigo and Habit, as well as memorable episodes in Fear Itself and The ABCs of Death 2, while also producing work within the genre and being a character actor in his own right.

To celebrate the 200 years of the writing and publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 2018, many events took place all over the world, many publications and symposiums were held, but ultimately we didn’t get a great film to cap it all off, until today. Depraved, Fessenden’s latest film, is the definitive capper for that celebration, a fitting tribute to Mary Shelley and a modern enough spin for it to be exciting.

Depraved get things into motion quickly by claiming the life of the protagonist, played by Alex Breaux, to then turn him into Adam, a reanimated corpse done by the experimenting of Henry (played by David Call) and the cheekily named Polidori (magnificently performed by Joshua Leonard), who are testing out new methods to resucitate and bring forward the brain power through the rewiring of neurones.

The first half of the film is cleverly structured around montages that show the advance in Adam’s brain: doing puzzles, reading, talking, understanding scientific concepts and, above all, a beautiful sequence at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where we see Polidori touring Adam around the history of art and of humanity.

Eventually the film settles into the mystery that is the life of Adam before he was killed, as he tries to piece together where he came from and how he got there. Attentive viewers will have the answers for most of these questions, and will consider this the weakest segment of the film.

But it maintains itself interesting with multiple formal choices, which are a continuation of the choices made by Fessenden to race through the usual motifs associated with the Frankenstein film: animated overlays over the action, distinct camera qualities to show memories or security footage, visual nods to earlier Frankenstein movies and classic horror, among others, which puts this film as a love letter to the genre lovers.

The succint editing and the clever points of view present in the camera angles make up for a lot of the absence in character development, which might be the film’s weakest point, as we don’t get to know too much of the two scientists that are doing the Adam project. Polidori just comes off as some knowledgeable asshole, while Henry is just a caring, loving, nervous prick that seems to change his will at the flip of a switch.

That doesn’t matter as much as the development of Adam himself, who is the star of the film. Since he’s a blank slate, we see him evolving and creating a perspective and feelings of his own, even if his monotone grovelling voice might distract, Alex Breaux is the best performer in this movie.

The film feels satisfactory because of how clever it pieces together the elements that we already know about and how it introduces technology and elements from real life to generate the definitive Prometian tale of the decade. It’s a surprisingly entertaining film that speaks enough about what is humanity, while having quite a bit of fun as well.

The definitive “gag”, if there is one, is a long sequence that shows us how Adam might be in the search of his “bride”, just like in the classic novel, but a bit sadder, funnier and wittier.

Slash Film

Chris Evangelista, 6/2/19

Larry Fessenden Gives New Life to Frankenstein with Depraved

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has been adapted so many damn times that you might think there’s nothing left to do with the story. But that didn’t deter indie horror legend Larry Fessenden from giving it a go. Fessenden has spent the last few years producing and acting, and his only directorial output has been in the form of shorts. Depraved marks his return to feature filmmaking for the first time since 2013, and the results don’t disappoint. In his time away from feature films, Fessenden has only grown stronger as a filmmaker, and Depraved ends up being his most visually stunning film to date. Fessenden directs the hell out of this thing, full of dreamy visual overlaps, graphic illustrations, montages, and immersive point-of-view shots. It’s a wonder to watch.

Depraved brings Frankenstein into the 21st century, opening with a scene of domestic bliss turned into domestic dispute as nervous Alex (Owen Campbell) ends up in a fight with his girlfriend Lucy (Chloë Levine, an actress who is becoming a familiar, and welcomed, face in the indie horror scene). Lucy wants kids, but Alex is horrified at the idea, and after a brief emotional blow-up, he decides to go back to his own apartment. The couple part ways awkwardly, but not bitterly. Alex assures Lucy they’ll continue their conversation tomorrow, but that doesn’t happen. Because on the stroll home through the New York streets, Alex is brutally stabbed to death.

This being a Frankenstein story, death is only the beginning. Alex is brought back to life, stitched together with new body parts as a taller, more muscular figure named Adam (now played by Alex Breaux). He has no memory of his past life. In fact, he doesn’t really know much of anything. He’s like a giant newborn. And he has only his “father”, a doctor named Henry (David Call) to care for him. Henry is a former field surgeon with PTSD who is working with an old buddy (Joshua Leonard) to develop a method of raising the dead.

Adam and Henry bond over the first half of the film, and here is where Depraved shines brightest. Fessenden is leaning into the Frankenstein story elements that focus on just what it is to be human, and watching Henry help his creation learn to talk, and interact, and become more social, is surprisingly emotional. That emotion is backed-up by a swooning, heartbreaking score courtesy of Will Bates.

Of course, this wouldn’t be a Frankenstein story without something going wrong. Adam’s inner turmoil about who and what he is begins to become a serious problem – with deadly consequences. Sadly, it’s here where Depraved stumbles a bit. After a near-perfect first two acts, Fessenden moves the action to a new location – a house full of people as a storm rages outside. It’s obvious the filmmaker is paying tribute to Frankenstein‘s origins – dreamed-up on one dark and stormy night as part of a ghost story-telling parlor game. But this chunk feels completely disconnected from everything that came before, and drags on.

No matter: the rest of Depraved is strong. The film is surprisingly sweet and melancholic – it aches with the soul of a poet. And the make-up effects used to bring Adam to life are convincingly icky. I went into Depraved wondering if we needed yet another Frankenstein adaptation. I left realizing I had just experienced one of the best.

COMICCON.COM

MLMiller, 3/29/2019

DEPRAVED isn’t the first time Larry Fessenden has delved into the Frankenstein mythos. The Godfather of Indie Horror Cinema played with reanimation in one of his first films, the mad science drama NO TELLING. That was 1991 and even though NO TELLING was a memorable and powerful film, Fessenden has perfected his distinct style and delivered a stunning low fi masterpiece in DEPRAVED.

Fessenden brings Mary Shelley’s tale into the modern age, following a PTSD afflicted war medic named Henry (David Call) who pairs up with an opportunistic pharma businessman named Polidori (BLAIR WITCH PROJECT’s Joshua Leonard) to test their new experimental drug on a recent murder victim. Naming the reanimated victim Adam (Alex Breaux), Henry goes about his private rehabilitation in a meticulous and careful manner – teaching Adam basic coordination and memory skills. Of course, this isn’t fast enough results for Polidori. Meanwhile, Adam is having flashes of his previous life and urges to find a mate of his own, much like Henry’s devoted girlfriend Liz (Ana Kayne). You know where this is going…and it’s going to be bad.

Fessenden hits all of the story beats we’ve seen in tons of reinterpretations of the Shelley classic. The difference here is that Fessenden distills the basics from the story and applies it to a modern tale of big pharma, lofty ambition, and the conflict between corporate demand vs. humanitarian treatment. Despite those heady themes, DEPRAVED is drenched with character and heart all around, as Fessenden imbues both Henry and Adam with sympathetic traits. Henry wants what’s best for Adam, looking after him like a child. But this treatment isn’t happening fast enough by Polidori, who is desperate to report results and make money off of all of this. This conflict is one of two in this tale, paralleled with Adam’s struggle to regain his humanity. All elements work marvelously and reflects Shelley’s tale in an intricate way that most Frankenstein tales fail.

Another thing that sets this film apart is Fessenden’s unique cinematography. Fessenden uses quick montages of images, simple overlays of color and light, and other rudimentary (but effective) camera effects that gives even more substance and style. This is a technique Fessenden has used before in films such as WENDIGO and THE LAST WINTER. Though this technique has been used by other directors (Aronofsky’s REQUIEM FOR A DREAM, for example), it feels like Fessenden’s unique stamp on each of his films. I would love to see Fessenden get his hands on a big budget film. He has been behind the scenes for way too long and has been a major trumpeter for many of the best voices in today’s horror game. Maybe he is comfortable with the low budget control and personal take to all of his own films, but I’d love to see what this soulful and passionate filmmaker would do with a couple of mill. That said, DEPRAVED is truly one of the best FRANKENSTEIN adaptations you’re going to find. Be on the lookout for it.

Alien Bee

3/21/2019

Movie Review: DEPRAVED

DEPRAVED was written, produced, edited and directed by Larry Fessenden and stars David Call, Joshua Leonard, Alex Breaux, Ana Kayne, Maria Dizzia, Chloë Levine, Owen Campbell and Addison Timlin.

Shot on the 200th Anniversary of Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN, veteran genre writer-director Larry Fessenden’s brings his unique vision of the literary classic in DEPRAVED, set in modern Brooklyn. This meditative reimagining of the novel explores the crisis of masculinity and ideas about loneliness, memory and the subtle psychological shocks that shape us as individuals.

Alex (Owen Campbell) leaves his girlfriend Lucy (Chloë Levine) after an emotional night, walking the streets alone to get home. From out of nowhere, he is stabbed in a frenzied attack, with the life draining out of him. He awakes to find he is the brain in a body he does not recognize. This creature, Adam (Alex Breaux), has been brought into consciousness by Henry (David Call), a brilliant field surgeon suffering from PTSD after two tours in the Mideast, and his accomplice Polidori (Joshua Leonard), a predator determined to cash in on the experiment that brought Adam to life. Henry is increasingly consumed with remorse over what he’s done and when Adam finally discovers a video documenting his own origin, he goes on a rampage that reverberates through the group and tragedy befalls them all.

The opening scene of Depraved shows Alex and Lucy parting ways and maybe it’s not on the best of terms. The next thing we see is Alex being viciously stabbed multiple times in an alley and waking up in on a makeshift operating table in a warehouse where he has no memory of his former life. When he looks in the mirror he sees a horribly scarred figure that’s been stitched together. This is when Henry introduces himself and names the figure Adam. The two quickly form a close bond as the creator slowly teaches his monster the basics and then a few other characters are introduced into the mix.

Polidori is Henry’s “partner in crime” and doesn’t really have Adam’s best interest at heart, so much so, he becomes trouble. While Adam is experiencing life at a rapid pace and remembering some of his past, Henry’s own traumatic experience from the war haunts him and has left the talented doctor scarred on the inside. This becomes a major issue for Polodori because the two aren’t on the same page when it comes to Adam who finally discovers his own shocking origin. This changes everything for everyone involved and now the experiment becomes a fight for survival for all parties. – especially Adam who now wants revenge.

Okay, we’ve gotten plenty of Frankenstein movies over the years and some that even tried to give the classic story a modern-day take but what Larry Fessenden has delivered is easily the best of these modern-day attempts and he did it on a shoestring budget. This impressive slice of indie cinema is not only the best modern-day take on Frankenstein but it adds just the right amount of flawed humanity and humility to it as well as real world problems – like PTSD. Even though Depraveddoes fit into the horror genre because of some of its graphic content like body parts, blood and gore, it’s also plays like a dramatic character study that focuses on the relationship between the monster and its creator as well as a love lost story that’s playing out in the background.

Depraved is more of a father and son or brotherly relationship because Henry has to reteach Adam so many things about life while bits and pieces of Adam’s memory quietly resurfaces. There’s also some troubling outside interference that comes into play that these two characters end up having to deal with. Needless to say, not everyone deals with these problematic situations the right way but that’s what being human is all about – right?

Bottom line is,, Larry Fessenden has taken Mary Shelley‘s classic story and created something fresh for the cinephiles out there to hopefully enjoy and appreciate as much as I did. He definitely made the best out of this ambitious micro-budget production and the proof is on the screen. The small cast also did their part because all of the characters are interesting – especially the two male leads. Something else that stands out in the movie are the fantastic makeup effects that help in creating the heavily scarred monster. All in all, I’ll go ahead and check this one off as an instant classic because this modern-day Frankenstein story has a lot of heart and is Fessenden’s best work to date.

We Got This Covered

Matt Donato, 3/22/2019

Larry Fessenden’s Depraved is a do-it-yourself Frankenstein adaptation that surges with the filmmaker’s passion for profession, material, and genre. Brooklyn warehouse districts and Manhattan’s underbelly play backdrop to a retelling steeped in its own mad scientifics. An “indie” stitched together by graverobber prosthetic effects, pop-savvy hallucinations of firing synapses, and “man or monster” duplicity rooted in Mary Shelley’s thematic prose but adaptive to relevant social climates. Empathy and tragedy befall what we’ve discovered to be the faulted human condition; ghastly designs merely a metaphor. As history repeats and civilization progresses, so does cinematic culture – with Fessenden on the forefront of depicting how to do so (on a shoestring budget) correctly.

Alex Breaux stars as Adam, a laboratory (Gowanus loft) creation at the hands of ex-military field surgeon Henry (David Call). Adam’s brain locks away his previous life – in a different body (Alex, played by Owen Campbell) – and as Henry teaches his “experiment” to become human once again, breadcrumbs of a past existence come in sudden flashbacks. Time passes, Adam’s cognitive and motor abilities regain strength, but Henry begins to doubt Adam’s readiness for public announcement despite his backer Polidori’s (Joshua Leonard) hasty desire to bring “RapX” in front of pharmaceutical investors. The more Polidori pushes, the angrier Henry gets, and the less control both men have over Adam.

Cinematographer James Siewert partners with Fessenden on multiple levels of intrigue, from black-and-white Universal Monsters callbacks to psychotropic colorization as in Glass Eye Pic’s Like Me (another Siewert collaboration). The latter reveals developmental awakenings of Adam’s mind, as green and blue pulses overtake the screen whenever Henry reaches a new milestone in tutelage – completed puzzles, ping-pong coordination, bouncing a rubber ball up and down. We aren’t treated to the most *lavish* locations, sticking to New York City back alleys and nondescript rentals, but bursts of anatomy books and neurological x-rays atop Adam’s montages do accentuate visual storytelling.

Makeup design by Peter Gerner and Brian Spears transform Breaux’s toned and slender figure into a composite of sewn together assorted limbs, sliding threads through flesh with abominable results. Crosshatches run up-and-down Adam – circling one eye and mismatching ear skin on another side – as Henry’s macabre Humpty Dumpty stays put together by modern medical marvels. In such a low-fi project, grotesqueries like splitting seams and surgeon-precise attachments aren’t always…presentable. Good thing Depraved succeeds under the scalpel, unafraid to showcase its childlike amalgamation of decomposed connectors under spotlights.

As Adam proceeds through mental hurdles to regain human features, Fessenden mirrors the rapid-fire speed in which we live our lives. Henry’s PTSD from Middle East combat leaves behind crushing guilt for every soldier he couldn’t save – hence his desire to cheat unknown powers and natural causes. Polidori – the business-blunt moneyman who takes Adam to strip clubs, feeds him whiskey – embraces the role of obstructer to Henry’s tender care-taking. Adam is brought into this world a specimen, but also an empty soul.

He’s viewed a freak, failed by those around him as intentions turn toxic, and all while he attempts to find the simplest of pleasures – human compassion. Brutishness and loneliness blur as Fessenden introduces Henry’s on-off girlfriend Liz (Ana Kayne), a flirty-friendly barfly who sparks Adam’s excitement (played by Addison Timlin), and the horrors of one man’s incapability to keep stride with an ever-changing society shaped by repulsion.

It’s nothing new in terms of Frankenstein lore, but performances spark this hipster’s cadaver feature to life. Between Breaux’s metamorphosis from a mute, bewildered vampiric husk of harvested organs into a lean cut of inquisitive frustration lead astray, to Call’s representation of the best motivations becoming weaponized in the wrong hands, there exists a heavy heartbeat inside Depraved’s core. Leonard ever the over-slick worm of a conspirator who cuts right to the basest of human mistakes – hubris. As Adam learns when tossing his ball, what goes up must come down. Polidori could have used the same lesson, as Leonard’s ambitious outrage melts like Icarus’ wings. A tale old as time, updated with leather jackets, sympathetic lamentation towards a beast, and resonance in Adam’s narration of “I have lied, and they told me not to care.” Corruption, thy name is “reality.”

What traps ensnare Depraved come in the second act, as Polidori’s introduction interrupts the touchstone emotionality in the pupil/mentor relationship between Adam and Henry. Always the instigator, Polidori remains more one-note and pointed in his actions. A necessary manipulator, but Adam and Henry’s reanimation into adolescence remains Fessenden’s throughline achievement. Henry the shaken, parental, and conscious inventor; Adam this personification of male ego as the women around him become pawns or worse. Leonard takes Polidori’s arc full-circle upon Act III’s the “castle siege” moment, but compassion is Fessenden’s ally – Polidori distracts to a degree.

Depraved isn’t as the title suggests. Rather, Larry Fessenden plights the folly of man in ways that remain intrinsically human despite his main character’s living dead affliction – specific attention paid to the word “men.” Henry’s Dr. Frankenstein sports a warm nurturer’s aura and gut-shredding confliction, while Breaux’s “The Creature” molds into the monster everyone warns of, or fears, or desires. Fessenden’s methods are understated, craftsmanship authentically blistered, and status as a jack-of-all-trades auteur unmatched on the indie circuit. To any aspiring filmmaker who’s been told “Don’t wait, go out there and make your movie” – no one embodies that phrase better than Larry Fessenden. Take note.

Voices & Visions

3/22/2019

Depraved (2019)

Depraved comes to life right from the get-go. We start out with a great folk song by Elizabeth & The Catapult called “More Than Enough” with direct lyrics that might hint at themes to come. Slowly after witnessing a couple experiencing the pains and pleasures of a long-term relationship, our protagonist Adam (Alex Breaux) is violently attacked on his way home. He awakens to discover he has been resurrected by an ambitious surgeon named Henry (David Call). This Doctor Frankenstein character isn’t a your typical mad depraved scientist, but rather a war-damaged ex-soldier suffering with PTSD. The sights that he witnessed on tour have also affected him as well as his desire to stop death. Filling the more traditional corruptive villain role we have Polidori (played by the great Joshua Leonard), who is in it for the money and notoriety of the experiment. Both are self-absorbed and troubled and have very different ways of “parenting” and/or manipulating Adam. Henry chooses to give him games and culture to the point of providing companionship, Polidori provides drugs and strippers and both ultimately cause a breakdown in Adam. It is their well-intentioned but ultimately self-destructive actions that shape him which touches on the protective, conflicted importance of a parental role in this day and age.

That’s just one of a few key ideas that Fessenden wants to explore in his parable. When it comes to dealing with outside influence or attraction, Adam is clearly quite vulnerable and susceptible in ways that are recognizably human throughout. The wonderful Addison Timlin shows up later as a kindhearted, curious bar patron that wants to know Adam on a deeper level possibly. Where that scenario ends up might be familiar but also subversive since I was almost expecting the story to take us in to territory akin to The Bride Of Frankenstein. There’s also a central character named Liz (Ana Kayne) that strikes warm notes worth harmonizing with among the mostly male players here. Where it all ends up is both twisted and for the most part, quite nail-biting. Fessenden knows horror fans are incredibly aware of trappings, tropes and the glorious possibilities within the genre. Sadly, I think the very final act can’t quite stick the landing since it becomes confrontational in a way that almost feels inevitable. There’s still tension but I could’ve used a little more myself. Regardless, there’s a strong balance of pathos and empathy throughout the proceedings, that is almost audacious in of itself to not go too gory or too “depraved” as things progress.